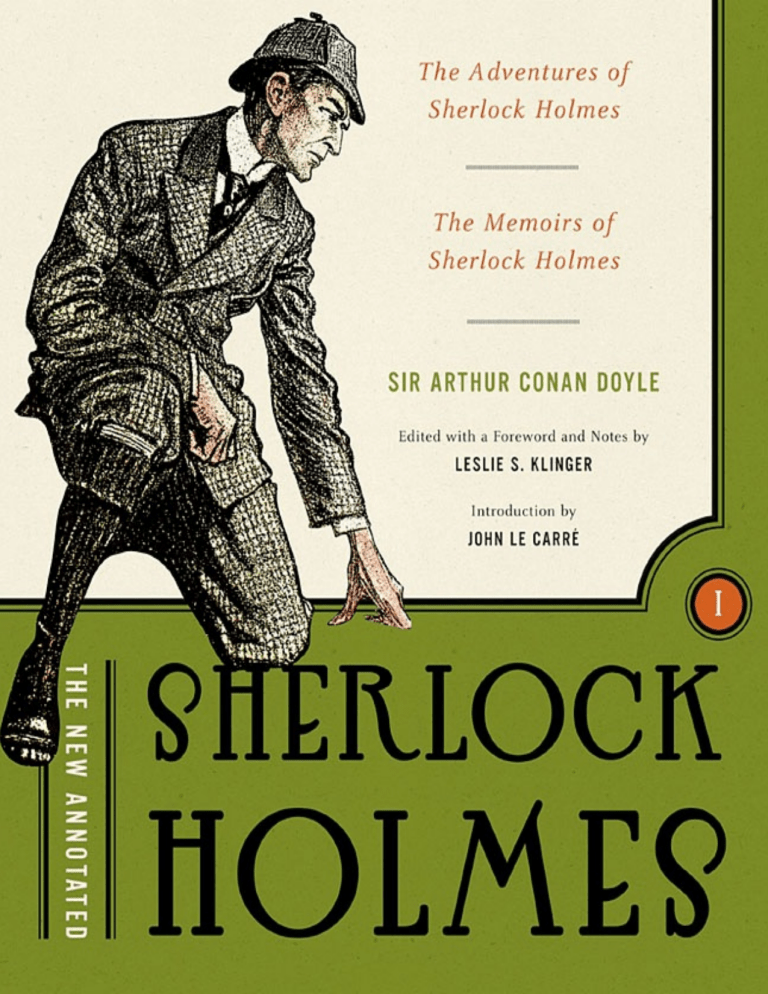

The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, Vol. 1 The Complete Short Stories The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and the Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes ( PDFDrive )

реклама