Sokolova M A Tikhonova I S Tikhonova R M Freydina E L - Theoretical Phonetics of English - 2010

реклама

CONTENTS

YD;K 8Il

EEK 81.2AHm

C59

COKOJlOBa

C59

M. A. H,!lJl.

TcopcTH"ICCKruI (j)OHCTHKa aHrJIHHcKOro H3bIKa /

HOM,

P. M. THxoHoBa, E. JI.

ISBN

(J)pcH,uHHa.

M. A

COKOJIOBa,

11. C. THXo-

D;y6Ha: (J)CHHKC+, 2010. -

192 c.

978-5-9279-0153-1

B yqc6HHKC H3JIafaJOTCH OCHOBbI TCOpCTJ:IlIeCKOfO Kypca (j)OHCTHKH aHrJIHHC­

KOfO H3bIKa.

B6

Introduction

6

1. Phonetics as a Linguistic Discipline

2. Divisions and Branchcs of Phonetics

3. Methods of Phonetic Investigation

4. Phonetics and Other Disciplines

5. Spheres of Practical Application

6

7

10

12

14

fJIaBaX YIIc6HHKa npC)J,CTaBJICHO orIHcaHHe (j)oHenI'ICcKoro

CTpmr COBpCMeHHOfO aHfJIHHcKOro H3bIKa H paCCMOTPeHbT np06JIeMhI HCrrOJIb30BaH.IDI (j)OHCTHIICCKHX C)J,HHI1IJ, B rrpoIJ,CCCC KOMMYHI1KaIJ,HH. Kypc HanpaBJIeH

Ha (j)OpMHpoBaHHc TCOpeTH'fCCKOH 6a3bI, Hco6xo;rJ:HMOH )J,JIH o6yqeHHH aHrJIHH­

Chapter I. The Functional Aspect of Speech Sounds ...................... 16

1.1. The Phoneme ........ ........................ ............................... 17

1.1.1. The definition of the phoneme ..................................... 17

1.1.2. The phoneme as a unity ofthrec aspects ....................... 18

1.1.3. Phonological and phonetic mistakes in pronunciation .... 23

CKOMY IlPOH3HOillCHHIO.

Y'le6HUIC npeOHG3Ha'leH Oilf/ cmyoeHmoeljJalCYllbmemoe UHocmpaHHblX Jl3b1ICOe ne­

Oa202U'leCICUX eY30e, a malC:HCe OjlJl UlUPOICOCO ICpY2a 'lumame;zeti, U3Y'laJOUJ,UX aH2­

J1UUCICUti Jl3b1IC U UHmepeCYIOUJ,uxCJl meopueu Jl3bllCa.

Y,llK 811

EEK 81.2AHrn

ISBN 978-5-9279-0153-1

1.2. Transcription ................................................................. 24

1.3. Main Trends in the Phoneme Theory ............................. 25

1.4. Methods of Phonological Analysis ................................. 28

1.4.1. The aim of phonological analysis ..................................

1.4.2. Distributional method of phonological analysis ............

1.4.3. Semantically distributional method ofphonological

analysis ........................................................................

1.4.4. Methods of establishing the phonemic status of speech

sounds in weakpositions. Morphonology ......................

© M. A. CoKOJIOBa, I1.. C. Tl1XoHoBa, P. M. TI1XOHOBa,

©

E. n. <I>peWlI1Ha, cO)J,ep)Kl!Hl1e, 2010

<I>CHHKC+, o<popMJIeHl1e, 2010

28

29

30

32

1. 5. The System of English Phonemes .................................. 34

1.5.1. The system of consonants .............................................

1.5.2. The system of vowels ....................................................

1.5.3. Modifications of sounds in connected speech ...............

1.5.3.1. Modifications of consonants ...........................

1.5.3.2. Modifications of vowels ...................................

M. A. COKOJIOBa, H. C. THxoHoBa, P. M. THXOHOBa, E. JI. <l>petf,llHHa

TEOPETIIqECKAH <l>OHETIIKA AHrJIIIHCKOrO H3blKA

PC)J,aKTOp O. E. CaaKJI.u

KOMl1bTOTCPHblll HaGop H. If. UIefJ'tyIC

KOMITbTOTCpHaJ'l BCPCTKaA.H. MUMue6

,[\113allH OMO)l(KH C. IO. UIeudpulC

<I>opMaT 60 x 90

V'6' THpa2K 2000 ::!K3. 3aKa3 N2 K-2539.

«<I>eHI1KC+». 141983, MocK. 06)1., r. ,[\y6Ha, yJI. TBepcKM, )J,.6A, 0<1>.156.

http://www.phoenix.dubna.ru

E-mail: pat&uk@dubna.ru

OmeqaTalIO B fYll.HfIK "qYBamlH!~

428019, r. Qe6oKcapbI, rIp. I1.. 5lKOBJIeBa, 13

35

39

45

45

47

Summary ...................................................................... 48

Chapter n.

2.1.

2.2.

2.3.

2.4.

Syllabic Structure of English Words

The Phenomenon of the Syllable

Syllable Formation

Syllable Division (Phonotactics)

Functional A'lpect ofthe Syllable

Summary

5]

51

53

53

55

56

4

Contents

Chapter III. Word Stress ................................................................... 57

3.1. Definition. The Nature of Stress. ....................... ............ 57

3.2. English Word Stress. Production and Perception ............ 59

3.3. Degrees ofWord Stress .................................................. 60

3.4. Placement ofWord Stress .............................................. 61

3.5. Tendencies in the Placement of Word Stress ................... 64

3.6. Functions ofWord Stress ............................................... 65

Summary ...................................................................... 66

Chapter rv. Intonation..................................................................... 68

Definition ofIntonation ................................................ 68

4.2. Components of Intonation ............................................ 70

5

Contents

5.2. Stylistic Modifications of Speech Sounds ..................... 114

116

Stylistic Use of Intonation

116

5.3.1. Phonostyles and their registers

118

5.3.2. Infonnational style

118

a) spheres of discourse

120

b) informational texts (reading)

c) informational monologues (speaking)

123

128

infonnational dialogues

133

e) press reporting and broadcasting

137

5.3.3. Academic style

140

5.3.4. Publicistic style

144

5.3.5. Declamatory style. Artistic reading

148

5.3.6. Conversational style

156

Summary

4.3. Intonation Pattern as the Basic Unit of I.n.tonation ......... 72

4.4. Notation ....................................................................... 78

Chapter VI. Social and Territorial Vctrieties of English ..................... 158

4.5. Functions ofIntonation ................................................ 79

4.5. L Communicative function as the basic function

of intonati on

79

4.5.2. Distinctive function

81

4.5.3. Organising function

85

4.5.4. Intonation in discourse

88

4.5.5. Pragmatic function

93

4.5.6. Rhetorical function

95

4.6. Rhythm

........... 96

4.6.1. Speech rhythm. Definition. Typology ........................... 96

4.6.2. Rhythmic group as the basic unit ofrhYlhm .................. 98

4.6.3. Rhythm in different types of discourse .......................... 98

4.6.4. Functions of rhythm .................................................. 101

Summary .................................................................... l02

6.1. Social Phonetics and Dialectology ............................... 158

Chapter V. Phonostylistics ........... ......... ......................... ....... ........ 105

5.1. The Problems ofPhonostylistics ..................................

5.1.1. Phonostylistics as a bmnch of phonetics .....................

5. 1.2. Extmlinguistic situation and its components ..... ..........

5.1.3. Style-fonning factors .................................................

5.1.4. Classification of phonetic styles .................. ................

105

105

107

109

112

6.2. Spread of English ........................................................ 162

6.3. English-based Pronunciation Standards of English ......

6.3.1. British English ...........................................................

6.3.2. Received pronunciation .............................................

6.3.3. Changes in the standard .............................................

6.3.4. Regional non-RP accents of England .........................

6.3.5. \\elsh English .............................................................

6.3.6. Scottish English .........................................................

6.3.7. Northern Ireland English ...........................................

6.4. American-based Pronunciation Standards of English ...

6.4.1. General American

Summary

References

163

163

164

166

172

177

178

180

182

183

188

190

INTRODUCTION

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Phonetics as a Linguistic Discipline

Divisions and Branches of Phonetics

Methods of Phonetic Investigation

Phonetics and Other Disciplines

Spheres of Practical Application

1. Phonetics as a Linguistic Discipline

This book is aimed at future teachers of English. The teachers of a for­

eign language are definitely aware of the existence of phonetics. They are

always being told that it is essential that they should be skilful phoneticians.

The reaction may be different. Some teachers meet it with understanding.

Some protest that it is not in their power for various reasons to become pho­

neticians, others deny that it is really necessary.

"Is it in fact necessary for a language teacher to be a phonetician? I

would reply that all language teachers willy-nilly are phoneticians. It is not

possible, for practical purposes, to teach a foreign language to any type of

learner, for any purpose, by any method, without giving some attention to

pronunciation. And any attention to pronunciation is phonetics." (Aber­

crombie, 1956: 28)

What does phonetics study? Phonetics is concerned with the human

noises, by which the thought is actualized or given audible shape: the nature

of these noises, their combinations, and their functions in relation to

meaning. Phonetics studies the sound system ofthe language, i. e. segmen­

tal phonemes, word stress, syllabic structure and intonation. It is primarily

concerned with expression level. However, phonetics takes the content

el into consideration too. Only meaningful sound sequences are regarded as

speech, and the science ofphonetics , in principle at least, is concerned only

with such sounds produced by a human vocal apparatus as are, or may be,

carriers of organized information of language. In other words, phonetics is

concerned both with the expression level ofphonetic units and their ability

to carry meaning. No kind oflinguistic study can be made without constant

consideration of the material and functional levels.

It follows from this that phonetics is a basic branch of linguistics; nei­

ther linguistic theory nor linguistic practice can do without phonetics, and

7

2. Divisions and Branches of Phonetics

no language description is complete without phonetics, the science con­

cerned with the spoken medium oflanguage. That is why phonetics claims

to be of equal importance with grammar and lexicology.

2. Divisions and Branches of Phonetics

Traditionally phonetics is divided into general phonetics which studies

the complex nature of phonetic phenomena and formulates phonetic laws

and principles and special phonetics which is concerned with the phonetic

structure ofa particular language. Admittedly, phonetic theories worked out

by general phonetics are based on the data provided by special phonetics

while special phonetics relies on the ideas of general phonetics to interpret

phonetic phenomena of a particular language.

Special phonetics can be subdivided into descriptive and historical. Spe­

cial descriptive phonetics studies the phonetic structure ofthe language syn­

chronically, while historical phonetics looks at it in its historical develop­

ment, diachronically. Historical phonetics is part of the history of the

language. The study ofthe historical development ofthe phonetic system of

a language helps to lmderstand its present and predict its future.

Another important division of phonetics is into segmental phonetics,

which is concerned with individual sounds (1. e. "segments" of speech) and

suprasegmental phonetics whose domain is the larger units of connected

speech: syllables, words, phrases and text.

Figure 1

phonetics

segmental

phonetics

suprasegmental

phonetics

Phonetics has two aspects: on the one hand, phonology, the study of the

functional aspect of phonetic units, and on the other, the study of the sub­

stance of phonetic units.

Before analysing the linguistic function of phonetic units we need to

know how the vocal mechanism acts in producing oral speech and what

8

Introduction

methods are applied in investigating the material form of the language, in

other words its substance.

Human speech is the result ofa highly complicated series of events. The

formation of the message takes place at a linguistic level, i. e. in the brain of

the speaker; this stage may be called psychological. The message formed in the

brain is transmitted along the nervous system to the speech organs. Therefore

we may say that the human brain controls the behaviour of the articulating

organs which results in producing a particular pattern ofspeech sounds. This

second stage may be called physiological. The movements of the speech ap­

paratus disturb the air stream thus producing sound waves. Consequently the

third stage may be called physical or acoustic. Further, any communication

requires a listener, as well as a speaker. So the last stages are the reception of

the sound waves by the listener's hearing physiological apparatus, the trans­

missiou of the spoken message through the nervous system to the brain and

the linguistic interpretation ofthe information conveyed.

Although not a single one ofthe organs involved in the speech mecha­

nism is used only for speaking we can for practical purposes use the term

"organs of speech", meaning the organs which are active, directly or indi­

rectly, in the process ofspeech sound production.

In accordance with their linguistic function the organs ofspeech may be

grouped as follows:

The respiratory or power mechanism furnishes the flow of air which is

the first requisite for the production of speech sounds. This mechanism is

formed by the lungs, the wind-pipe and the bronchi. The air-stream ex­

pelled from the lungs provides the most usual source of energy which is

regulated by the power mechanism. Regulating the force ofthe air-wave the

lungs produce variations in the intensity of speech sounds. Syllabic pulses

and dynamic stress, both typical of English, are directly related to the be­

haviour of the muscles which activate this mechanism.

From the lungs through the wind-pipe the air-stream passes to the up­

per stages ofthe vocal tract. First ofall it passes to the larynx containing the

vocal cords. The opening between the vocal cords is known as the glottis.

The function of the vocal cords consists in their role as a vibrator set in mo­

tion by the air-stream sent by the lungs. The most important speech func­

tion of the vocal cords is their role in the production of voice. The effect of

voice is achieved when the vocal cords are brought together and vibrate

when subjected to the pressure of air passing from the lungs. The vibration

is caused by compressed air forcing an opening ofthe glottis and the follow­

ing reduced air-pressure permitting the vocal cords to come together.

2. Divisions and Branches of Phonetics

9

The height of the speaking voice depends on the frequency ofthe vibra­

tions. The more frequently the vocal cords vibrate the higher the pitch is.

The typical speaking voice of a woman is higher than that ofa man because

the vocal cords of a woman vibrate more frequently. We are able to vary the

rate of the vibration thus producing modifications of the pitch component

of intonation. More than that. We are able to modify the size of the puff of

air which escapes at each vibration of the vocal cords, i. e. we can alter the

amplitude of the vibration which causes changes of the loudness of the

sound heard by the listener.

From the larynx the air-stream passes to supraglottal cavities, i. e. to the

pharynx, the mouth and the nasal cavities. The shapes of these cavities

modify the note produced in the larynx thus giving rise to particular speech

sounds.

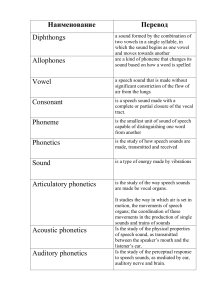

There are three branches of phonetics each corresponding to a different

stage in the communication process described above. Each ofthese branch­

es uses a special set of methods.

The branch of phonetics that studies the way in which the air is set in

motion, the movements of the speech organs and the coordination of these

movements in the production of single sounds and trains ofsounds is called

articulatory phonetics. Articulatory phonetics is concerned with the way

speech sounds are produced by the organs of speech, in other words the

mechanisms of speech production.

Acoustic phonetics studies the way in which the air vibrates between the

speaker's mouth and the listener's ear, in other words, the sound wave.

Acoustic phonetics is concerned with the physical properties of speech

sounds and uses special technologies to measure speech signals.

The branch of phonetics investigating the perception process is known

as auditory phonetics. Its interests lie more in the sensation ofhearing which

is brain activity, than in the physiological working of the ear or the nervous

activity between the ear and the brain. The means by which we discriminate

sounds - quality, sensation of pitch, loudness, length, are relevant here.

branch of phonetics is of special interest to anyone who teaches or

studies pronunciation.

As it was mentioned above, phoneticians cannot act only as describ­

ers and classifiers of the material form of phonetic units. They are also

interested in the way in which sound phenomena function in a particular

language and what part they play in manifesting the meaningful distinc­

tionsofthe language. The branch of phonetics that studies the linguistic

function of consonant and vowel sounds, syllabic structure, word accent

Introduction

10

and prosodic features, such as pitch, loudness and tempo is called pho­

nology.

In linguistics, function is usually understood as discriminatory func­

tion, that

the role of the various elements ofthe language in the distin­

guishing ofone sequence of sounds, such as a word or a sequence ofwords,

from another of different meaning. Though we consider the discriminatory

function to be the main linguistic function of any phonetic unit we cannot

ignore the other function of phonetic units, that is, their role in the forma­

tion ofsyllables, words, phrases and texts. This functional or social aspect of

phonetic phenomena was first introduced by I. A. Baudouin-de-Courtenay.

Later on N. S. Trubetskoy declared phonology to be a linguistic discipline

and acoustic phonetics to anatomy, physiology and

acoustics only. This conception is shared by many foreign linguists who in­

vestigate the material form and the function of oral speech units separately.

Russian linguists proceed from the view that language is the medium of

thought and can exist only in the material form of phonetic units. That is

why they consider phonology a branch of phonetics that investigates its

most important social aspect.

2

Branches of Phonetics

articulatory

phonetics

auditory

phonetics

acoustic

phonetics

functional phonetics

(phonology)

3. Methods of Phonetic Investigation

Each branch of phonetics uses its own methods of research. We shall

consider now some ofthe methods applied in investigating the sound matter

ofthe language.

They generally distinguish methods of direct observation (phonetic

studies are carried out without any other instruments of analysis than the

human senses) and instrumental methods based on the use ofvarious

nical devices.

From the beginning of phonetics the phonetician has relied to a great

extent on the perception ofhis own speech and the informants' speech. The

3. Metods of Phonetic Investigation

11

experience in such observation allows him to associate the qualities of the

sound heard with the nature ofthe articulations producing it. Such skills are

obligatory for phoneticians and make phonetics not only a science but also

an art, an art which must be specially learned. Phonetic research based on

the methods of direct observation is effective only when the scholars con­

ducting it are trained in analyzing both the movements of the organs of

speech and the auditory impression of speech segments.

Instrumental methods were introduced into phonetics in the second half

ofthe 19th century in order to supplement the impressions deriving from the

human senses, especially the auditory impressions, since these are affected

by the limitations of the perceptual mechanism, and in general are rather

subjective.

Instrumental analysis is based on the use of special technical devices,

such as spectrograph, intonograph, x-ray photography and cinematogra­

phy, laryngoscope and others. In a general way, the introduction of ma­

chines for measurements and for instrumental analysis into phonetics has

resulted in their use for detailed study ofmany ofthe phenomena which are

present in the sound wave or in the articulatory process at any given mo­

ment, and the changes ofthese phenomena from moment to moment. This

type of investigation together with sensory analysis is widely used in experi­

mental phonetics.

The results available from instrumental analysis supplement those avail­

able from sensory analysis. Practically today there are no areas of phonetics

in which useful work can and is being done without combining these two

ways of phonetic investigation. The "subjective" methods of analysis by

sensory impression and the "objective" methods of analysis by instruments

are complementary. Both "objective" and "subjective" methods are widely

used in modern phonetics. Articulatory phonetics borders with anatomy

and physiology, it uses methods of direct observation, whenever it is possible

(lip movement, some tongue movement) combined with x-ray photography

or x-ray cinematography, observation through mirrors as in the laryngo­

scopic investigation of vocal cord movement, etc.

Acoustic phonetics comes close to physics and the tools used in this

field enable the investigator to measure and analyse the movement ofthe air

in the terms of acoustics. This generally means introducing a microphone

into the speech chain, converting the air movement into corresponding

electrical activity and analysing the result in terms of frequency ofvibration

and amplitude of vibration in relation to time. The use of various sound

analysing and sound synthesising machines is generally combined with the

12

Introduction

method of direct observation. Today computer technologies make it possi­

ble to conduct acoustic spectral analysis ofspeech sounds and intonograph­

ic analysis.

It should be mentioned that computer technologies are widely used

both for processing and measuring acoustic data and for pronunciation

training. One of the advantages of using computers for the experimental

study is the possibility of storing substantial corpora of various spoken dis­

course to serve as the material for phonetic investigation.

Phonology possesses its own methods ofinvestigation which will be de­

scribed later in the course.

4. Phonetics and Other Disciplines

Our further point will be made in connection with the relationship of

phonetics and other disciplines. As it was already mentioned phonetics is

one of the basic branches of linguistics, naturally it is closely connected

with the other linguistic disciplines: lexicology and grammar.

Special attention should be given to the relations of phonetics and social

sciences. Language is not an isolated phenomenon; it is a part of society, a

part of ourselves. The functioning of phonetic units in society is studied by

sociophonetics. It should be mentioned here that over the last few decades

there appeared a number ofdistinct interdisciplinary subjects, such as socio­

linguistics (and sociophonetics correspondingly), psycholinguistics, mathe­

maticallinguistics and others. These, as their titles suggest, refer to aspects of

language which can be studied from two points ofview (sociology and linguis­

tics, psychology and linguistics and so on), which requires awareness and de­

velopment of concepts and the techniques derived from both disciplines.

Sociophonetics studies the ways in which pronunciation interacts with

society. In other words, it is the study of the way in which phonetic struc­

tures change in response to different social functions. Society here is used in

its broadest sense, to cover a spectrum of phenomena such as nationality,

regional and social groups, and specific interactions of individuals within

them. There are innumerable facts to be discovered and considered, even

about a language as well investigated as English, concerning, for instance,

the nature ofthe different situations - when we are talking to equals, supe­

riors or subordinates; when we are 'on the job', when we are old or young;

male or female; when we are trying to persuade, inform, agree or disagree

and so on. Needless to say sociophonetic information is of crucial impor­

4. Phonetics and Other Disciplines

13

tance for language teachers and language learners in the context of cross­

cultural communication.

One more example ofinterdisciplinary overlap is the relation oflinguis­

tics to psychology. Psycholinguistics as a distinct area ofinterest developed

the sixties, and in its early form covered the psychological implications of

an extremely broad area, from acoustic phonetics to language pathology.

Nowadays no one would want to deny the existence ofstrong mutual bonds

between linguistics, phonetics in our case and psychology. Here are some of

the problems covered by psycholinguistics: the acquisition of language by

children, the extent to which language meditates or structures thinking;

extent to which language is influenced and itself influences such things as

memory, attention, perception; the problems of speech production and

speech perception; speech pathology.

Phonetics is also closely connected with a number ofnon-linguistic dis­

ciplines which study different aspects ofspeech production and speech per­

ception: physiology, anatomy, physics (acoustics). In phonetic research

they use mathematics, statistics, computer science.

There is one more area phonetics is closely connected with. It is the

study of non-verbal means ofcommunication.

How do people communicate?

Too often there is a difference between what we say and what we think

we have said, though we use appropriate grammatical structures, words and

intonation. It may even cause a break in communication.

It may happen because we speak with our oral organs, but we converse

with our entire bodies. Conversation consists of much more than a simpJe

interchange ofspoken words. All ofus communicate with one another non­

verbally. It means that we communicate without using words and involving

movements of different parts of the body.

It is believed that 7% of communication is conveyed by words, 38%

by sounds and intonation and 55% - by non-verbal means. They are: facial

expression, gestures and postures.

D. Crystal insists that the meaning of particular nuclear tones depends

on the combination with particular facial expression.

Non-verbal elements express very efficiently the emotional or the mod­

al side of the message.

The study of non-verbal means of communication is called kinesics.

The analysis ofspoken discourse often includes references both to the pho­

netic and non-verbal aspects ofspeech communication. So we can say that

phonetics overlaps with kinesics.

Introduction

14

The field of phonetics is thus becoming wider and tends to extend over

the limits originally set by its purely linguistic applications. On the other

hand, the growing interest in phonetics is partly due to increasing recogni­

tion of the central position of language in every line of social activity. It is

important, however, that the phonetician should remain a linguist and look

upon phonetics as a study of the spoken form oflanguage. It is its applica­

tion to linguistic phenomena that makes phonetics a social science in the

proper sense of the word.

5. Spheres of Practical Application

Now we shall give an overview ofthe spheres in which phonetics can be

applied.

A study of phonetics has educational value for everyone, who realizes

the importance of language in human communication. Through the study

of the nature oflanguage, especially of spoken language, valuable insights

are gained into human psychology and into the functioning of a man in so­

ciety. That is why we dare say that phonetics has considerable social value.

The knowledge of the structure of sound systems, and of the articula­

tory and acoustic properties of the production of speech is indispensable

in the teaching of foreign languages. The teacher has to know the starting

point, which is the sound system of the pupil's mother tongue, as well as

the aim of his teaching, which is mastering the pronunciation of the lan­

guage to be learnt. He/she must be able to point out the differences be­

tween these two, and to provide adequate training exercises. Ear training

and articulation training are both equally important in modern language

teaching. The introduction of new technologies, computers in particular,

has brought about a revolution in the teaching of the foreign language

pronunciation.

In our technological age phonetics has become important in a number

oftechnological fields connected with communication. The results of pho­

netic investigations are used in communication engineering. Phonetic data

is obviously needed for creating sound analyzing and sound synthesizing

devices, for example machines converting the printed symbols or letters

into synthetic speech or automatic typewriters which convert speech di­

rectly into printed words on paper.

Phonetics contributes important information to the research in crimi­

nology aimed at identifying individuals by voices.

5. Spheres of Practical Application

15

For those who work in speech therapy, which handles pathological con­

ditions ofspeech, phonetics forms an essential part ofthe professional train­

ing syllabus. Phonetics also enters into the training of teachers of the deaf

and dumb people and can be of relevance to a number of medical and den­

tal problems.

Phonetics has proved extremely useful in such spheres as investigations

in the historical aspects of languages, in the field of dialectology; designing

or improving systems of writing or spelling (orthographies for unwritten

languages, shorthand, spelling reform), in questions involving the spelling

or pronunciation of personal or place names or of words borrowed from

other languages.

At the faculties of foreign language in this country two courses of pho­

netics are introduced: practical and theoretical phonetics.

Practical or normative phonetics studies the substance, the material

form of phonetic phenomena in relation to meaning.

Theoretical phonetics is mainly concerned with the functioning ofpho­

netic units in the language. Theoretical phonetics, as we introduce it here,

regards phonetic phenomena synchronically without any special reference

to the historical development of English.

This course is intended to discuss the problems of phonetic science

which are relevant to English language teaching. The teacher must be sure

that what he/she teaches is linguistically correct. In this course we are to

bring together linguistic theory and EFL practice. We hope that this book

will enable the teacher to work out a truly scientific approach to pronuncia­

tion teaching.

In phonetics as in any other discipline, there are various schools whose

views sometimes coincide and sometimes conflict. Occasional reference is

made to them but there is no attempt to describe and compare all possible

traditional and current approaches to the phonetic theory.

As you see from the above, the purpose of this book is to consider the

role of phonetic means in communication and to serve as a general intro­

duction to the subject of theoretical phonetics of English which will en­

courage the student and the teacher of English to consult more specialized

works on particular aspects.

The authors ofthe book hope that the readers have sufficient knowledge

of the practical course of English phonetics as well as of the course of gen­

erallinguistics, which will serve as the basis for this course.

The description of the phonetic structure of English will be based on

Received Pronunciation (RP).

Chapter I

THE FUNCTIONAL ASPECT

OF SPEECH SOUNDS

This chapter is concerned with the linguistic function of speech sounds,

i. e. "segments of speech".

We are going to discuss here the defInitions of the phoneme, methods

used in establishing the phonemic structure of a language, the system of

English phonemes, modifIcations of sounds in connected speech.

1.1. The Phoneme

1.1.1. The definition of the phoneme

1.1.2. The phoneme as a unity of three as­

pects

1.1.3. Phonological and phonetic mistakes in

pronunciation

1.2. Transcription

1.3. Main Trends in the Phoneme Theory

17

1.1. The Phoneme

1.1. The Phoneme

1.1.1. The defmition ofthe phoneme

To know how sounds are produced by speech organs it is not enough to

describe and classify them as language units. When we talk about the sounds

of a language, the term "sound" can be interpreted in two rather different

ways. In the fIrst place, we can say that [t] and [d] are two different sounds

in English, [t] being fortis and [d] being lenis 1 and we can illustrate this by

showing how they contrast with each other to make a difference of meaning

in a large number of pairs, such as tie die, seat seed, etc. But on the

other hand ifwe listen carefully to the [t] in let us and compare it with the

in let them we can hear that the two sounds are also not the same, the [t] of

let us is alveolar, while the [t] of let them is dental. In both examples the

sounds differ in one articulatory feature only; in the second case the differ­

ence between the sounds has functionally no significance. It is perfectly

clear that the sense of "sound" in these two cases is different. To avoid this

ambiguity, the linguist uses two separate terms: "phoneme" is used to mean

"sound" in its contrastive sense, and "allophone" is used for sounds which

are variants of a phoneme: they usually occur in different positions in

word (i. e. in different environments) and hence cannot contrast with each

other, nor be used to make meaningful distinctions.

1.4. Methods of Phonological Analysis

1.4.1. The aim of phonological analysis

1.4.2. Distributional method of phonological

analysis

1.4.3. SemanticaUy distributional method of

phonological analysis

1.4.5. Methods of establishing the phonemic

status of speech sounds in weak posi­

tions. Morphonology

1.5. The System of English Phonemes

1.5.1. The system of consonants

1.5.2. The system ofvowels

1.5.3. Modifications of sounds in connected

speech

1.5.3.1. Modifications of consonants

1.5.3.2. Modifications ofvowels

<! ... B )!{flBOH pel [11 rrpOH3HOCl1TCSl 3Ha'Il1TCJlbHO oOJIbruee, 'ICM Mhl OfihlKHOBeHHO ,llYMa­

eM, KOJU1'fCCTBO pa3Hoofipa3HbIX 3BYKOB, KOTOpb[e B Ka)!{;nOM ,llaHHOM ll3bIKe om,e,llH­

HHIOTCSl B cpaBHflTeJlbHO HefioJIbruoc 'IHCJlO :mYKOBhlX THIIOB, crrocofiHbIX ,llHcpcpepeH­

l\HpOBaTb CJlOBa H fiX CPOPMbl, T. e. CJIY)KHTb l\eJlJIM 'ICJIOBC'ICCKOro ofimeHHll. 3TH

3BYKOBblC THrrbl H HMCIOTCJI B BH;ny, KOr,lla roBOPliT 06 OT;nCJIbHhlX 3BYKaX pe'IlL Mbl

6Yil.eM Ha3bIBaTb fiX cpoHcMaMH. PCaJIbHO rrpOH3HOCHMble pa3JlH'Ufble 3BYKfI, SlBJISlIO­

IUHeCJI reM 'IaCTHbIM, B KOTOPOM peaJIH3YCTCJI 06mec (cpOHCMa), 6y)\eM Ha3blBaTb OT­

TCHKaMH cpOHCM. (Ill,ep6a,

1963:

And furthcr on:

«qeM )!{C orrpC)leJIJIeTC:;I 3TO o6ruce? O'IcBH;nHo, MMCHHO OfimCHIl.CM, KOTopoe

:;IBJIlieTCll OCHOBHOti: l\eJlblO JI3hlKa, T. e. B KOHe'fHOM C'IeTe CMbICJIOM: e,llHHblH CMbICJI

3aCTaRJlHCT Hac ,llll)!{e B GOJlee HJIM MCHCC pa3HbiX 3BYKllX Y3HaBaTb O,llHO H TO )!{e.

Ho H

,lI.aJIbmC, TOJlbKO TaKoe o6LUec B3iKJ:IO mlJI Hac B JIMHrBI1CTHKC, KOTopoe ,llHcpcpcpeHQll­

PYCT ,llaHHYIO rpyrrrry (CKa)!{CM pa3Hbie 'a') OT )lpyroti: rpynI1hl, HMClOmCH ,lI.pyrOH

CMbICJl (HarrpllMCp, OT COJ03a 'H', rrpOH3HeceHHoro rpOMKO, rucrrOTOM H T.,ll. ). BOT 3TO

o61IIee 11 Ha3bIBaeTCli cpoHeMofi. TaKHM 06pa30M, Ka)KtJ:aH cpOHeMa onpe,lleJIJIeTCSl rrpe­

)I()le BCCro 'I'eM, 'ITO OTJIfitlaeT ee OT ,llPYrllX cpOHeM TOfO )!{e Sl3blKa. DnarO,llapJI 3TOMY

Bce cpOHeMbI Ka)!{tJ:oro ,llaHHOro H3bIKa 06pa3YJOT C,llIlHYJO CllCTCMY I1POTHBOIIOJlO)!{­

HOCTeti:, r,llC KaiKJ:~b[H 'fJICH onpe,lleJIJICTCJI cepHCH pa3JlH'IHb[X rrpOTMBOIIOnO)!{CHHH KaK

OTil.CJIbHhlX CPOHCM, TaK H HX rpynrr».

Chapter 1. The Functional Aspect of Speech Sounds

18

The most comprehensive defmition ofthe phoneme was first introduced

by the Russian linguist L. V. Shcherba.

The concise form ofthis definition could be:

The phoneme is a minimal abstract linguistic uuit realized in speech in the

form of speech souuds opposable to other phonemes of the same language to

distinguish the meauing of morphemes and words.

According to this definition the phoneme is a unity of three aspects:

material, abstract and functional.

Figure 3

Three Aspects of the Phoneme

\.

Material aspect

)

(

Abstract

(

Functional aspect

\.

1.1.2. The phoneme as a uuity of three aspects

Let us consider the phoneme from the point of view of its three aspects.

Firstly, the phoneme is a functional unit. A" you know, in phonetics function is

usually understood as discriminatory function, i. e. the role ofvarious compo­

nents of the phonetic system of the language in distinguishing one morpheme

from another, one word from another or also one utterance from another.

The opposition of phonemes in the same phonetic environment differ­

entiates the meaning ofmorphemes and words: said - says, sleeper - sleepy,

bath - path, light -like.

Sometimes the opposition of the phonemes serves to distinguish the

meaning ofthe whole phrases: he was heard badly - he was hurt badly. Thus

we may say that the phoneme can fulfil the distinctive function.

Secondly, the phoneme is material, real and objective. That means that

it is realized in speech of all English-speaking people in the form of speech

sounds, its allophones. The sets of speech sounds, i. e. the allophones be­

longing to the same phoneme: I) are not identical in their articulatory con­

tent though there remains some phonetic similarity between them; 2) are

never used in the same phonetic context.

As a first example, let us consider the English phoneme [d], at least

those of its allophones which are known to everybody who studies English

pronunciation. As you know from the practical course ofEnglish phonetics,

1.1. The Phoneme

19

[d] when not affected by the articulation of the preceding or following

sounds is a plosive, forelingual apical, alveolar, lenis stop. This is how it

sounds in isolation or in such words as door, darn, down, etc., when it re­

tains its typical articulatory characteristics. In this case the consonant [d] is

called the principal allophone. The allophones which do not undergo any

distinguishable changes in the chain of speech are called principal. At the

same time there are quite predictable changes in the articulation of allo­

phones that occur under the influence ofthe neighbouring sounds in differ­

ent phonetic situations. Such allophones are called subsidiary.

The examples below illustrate the articulatory modifications ofthe pho­

neme [d] in various phonetic contexts:

[d] is slightly palatalized before front vowels and the sonorant [j], e. g.

deal, day, did, did you.

is pronounced without any plosion before another stop, e. g. bedtime,

bad pain, good dog; it is pronounced with the nasal piosion before the nasal

sonorants [n] and [m], e. g. sudden, admit, could not, could meet; the plosion

is lateral before the lateral sonorant [1], e. g. middle, badly, bad light.

The alveolar position is particularly sensitive to the influence of the

place ofarticulation ofa following consonant. Thus followed by [r] the con­

sonant [d] becomes post-alveolar, e. g. dry, dream; followed by the inter­

dental [9], [a] it becomes dental, e. g. breadth, lead the way, good thing.

When [d] is followed by the labial [w] it becomes labialized, e. g. dweller.

In the initial position [d] is partially devoiced, e. g. dog, dean; in the in­

tervocalic position or when followed by a sonorant it is fully voiced, e. g.

order, leader, driver; in the word-final position it is vQiceless, e. g. road,

raised, old.

These modifications of the phoneme [d] are quite sufficient to demon­

strate the articulatory difference between its allophones, though the list of

them could be easily extended. If you consider the production of the allo­

phones of this phoneme, you will fmd that they possess three articulatory

features in common: all of them are forelingual1enis stops.

Consequently, though allophones of the same phoneme possess similar

articulatory features they may frequently show considerable phonetic dif­

ferences.

It is perfectly obvious that in teaching English pronunciation the differ­

ence between the allophones of the same phoneme should be necessarily

considered. The starting point is of course the articulation of the principal

allophone, e. g. jd-d-dj: door, double, daughter, dark, etc. Special training

of the subsidiary allophones should be provided too. Not all the subsidiary

1.1. The Phoneme

Chapter I. The Functional Aspect of Speech Sounds

20

allophones are generally paid equal attention to. In teaching the pronuncia­

tion of [d], for instance, it is hardly necessary to concentrate on an allo­

phone such as [d] before a front vowel as in Russian similar consonants in

this position are also palatalized. Neither is it necessary to practise specially

the labialized [d] after the labial [w] because in this position [d] cannot be

pronounced in any other way. Carefully made up exercises will exclude the

danger of a foreign accent.

Allophones are arranged into functionally similar groups, i. e. groups of

sounds in which the members of each group are not opposed to one an­

other, but are opposable to members of any other group to distinguish

meanings in otherwise similar sequences. Consequently allophones of the

same phoneme never occur in similar phonetic context, they are entirely

predictable according to the phonetic environment and cannot differenti­

ate meanings.

But the speech sounds (phones) which are realized in speech do not

correspond exactly to the allophone predicted by this or that phonetic envi­

ronment. They are modified by phonostylistic, dialectal and individual fac­

tors. In fact, no speech sounds are absolutely alike.

Phonemes are important for distinguishing meanings, for knowing

whether, for instance, the message was take it or tape it. But there is more to

speaker-listener exchange than just the "message" itself. The listener may

get a variety of information about the speaker: about the locality he lives in,

regional origin, his social status, age and even emotional state (angry, tired,

excited), and a lot of other facts. Most ofthis social information comes not

from phonemic distinctions, but from phonetic ones. Thus, while phone­

mic evidence is important for lexical and grammatical meaning, most other

aspects of communication are conveyed by more subtle differences of

speech sounds, requiring more detailed description at the phonetic level.

There is more to a speech act than just the meaning ofthe words.

The relationships between the phoneme and the phone (speech sound)

may be illustrated by the following scheme:

Figure 4

phonostylistic variation

l

dialectal variation

individual variation

)--1

speech sound (phone)

I

21

Thirdly, allophones of the same phoneme, no matter how different

their articulation may be, function as the same linguistic unit. The ques­

tion arises why phonetically naive native speakers seldom observe differ­

ences in the actual articulatory qualities between the allophones of the

same phonemes.

The native speaker is quite readily aware of the phonemes of his lan­

guage but much less aware of the allophones: it is possible, in fact, that he

will not hear the difference between two allophones like the alveolar and

dental consonants [d] in the words bread and breadth even when a distinc­

tion is pointed out; a certain amount of ear-training may be needed. The

reason is that the phonemes have an important function in the language:

they differentiate words like tie and die from each other, and to be able to

hear and produce phonemic differences is part of what it means to be a

competent speaker of the language. Allophones, on the other hand, have

no such function: they usually occur in different positions in the word,

i. e. in different environments, and hence cannot be opposed to each oth­

er to make meaningful distinctions.

For example the dark [1] occurs following a vowel as inpi/l, cold, but

it is not found before a vowel, whereas the clear [1] only occurs before a

vowel, as in lip, like. These two consonants cannot therefore contrast with

each other in the way that [1] contrasts with [r] in lip - rip or lake - rake.

So the answer appears to be in the functioning of such sounds in a par­

ticular language. Sounds which have similar functions in the language

tend to be considered the "same" by the community using that language

while those which have different functions tend to be classed as "differ­

ent". In linguistics, as it has been mentioned above, function is generally

understood as the role of the various elements of the language in distin­

guishing the meaning. The function of phonemes is to distinguish the

meaning ofmorphemes and words. The native speaker does not notice the

difference between the allophones of the same phoneme because this dif­

ference does not distinguish meanings.

In other words, native speakers abstract themselves from the differ­

ence between the allophones of the same phoneme because it has no

functional value. The actual difference between the allophones of the

same phoneme [d], for instance, does not affect the meaning. That's

why members of the English speech community do not realize that in

the word dog [d] is alveolar, in dry it is post-alveolar, in breadth it is den­

tal. Another example. In the Russian word nocaaum the stressed vowel

[a] is more front than it is in the word nocaaKa. It is even more front in

22

Chapter 1. The Functional Aspect of Speech Sounds

the word CROem. But Russian-speaking people do not observe this differ­

ence because the three vowel sounds belong to the same phoneme and

thus the changes in their quality do not distinguish the meaning. So we

have good grounds to state that the phoneme is an abstract linguistic

unit, it is an abstraction from actual speech sounds, i. e. allophonic

modifications.

As it has been said before, native speakers do not observe the differ­

ence between the allophones of the same phoneme. At the same time they

realize, quite subconsciously of course, that allophones of each phoneme

possess a bundle ofdistinctive features, that make this phoneme function­

ally different from all other phonemes of the language concerned. This

functionally relevant bundle of articulatory features is called the invariant

of the phoneme. Neither of the articulatory features that form the invari­

ant ofthe phoneme can be changed without affecting the meaning. All the

allophones of the phoneme [d], for instance, are occlusive, fore lingual,

If occlusive articulation is changed for constrictive one [d] will be

replaced by [z], cf. breed - breeze, deal- zeal; [d] will be replaced by [g]

if the forelingual articulation is replaced by the backlingual one, cf. dear­

gear, day - gay. The lenis articulation of [d] cannot be substituted by the

fortis one because it will also bring about changes in meaning, cf. dry ­

try, ladder - latter, bid - bit. That is why it is possible to state that occlu­

sive, forelingual and lenis characteristics of the phoneme [d] are general­

ized in the mind of the speaker into what is called the invariant of this

phoneme.

On the one hand, the phoneme is real, because it is realized in speech

in the material form of speech sounds, its allophones. On the other hand,

it is an abstract language unit. That is why we can look upon the phoneme

as a dialectical unity of the material and abstract aspects. Thus we may

state that it is the material form of speech sounds, its allophones. Speech

sounds are necessarily allophones of one of the phonemes of the language

concerned. All the allophones of the same phoneme have some articula­

tory features in common, i. e. all of them possess the same invariant. Si­

multaneously each allophone possesses quite particular phonetic features

which may not be traced in the articulation of other allophones of the

same phoneme. That is why while teaching pronunciation we cannot ask

our students to pronounce this or that phoneme. We can only teach them

to pronounce one of its allophones.

The articulatory features which form the invariant of the phoneme are

called distinctive or relevant. To extract the relevant feature of the pho­

1.1. The Phoneme

23

neme we have to oppose it to some other phoneme in the same phonetic

context. If the opposed sounds differ in one articulatory feature and this

difference brings about changes in the meaning of the words the contrast­

ing features are called relevant. For example, the words port and court dif­

fer in one consonant only: the word port has the initial consonant [p], and

the word court begins with [k]. Both sounds are occlusive and fortis, the

only difference being that [p] is labial and [k] is backlingual. Therefore it

is possible to say that labial and backlingual articulations are relevant in

the system of English consonants.

The articulatory features which do not serve to distinguish meaning

are called non-distinctive, irrelevant or redundant; for instance, it is im­

possible in English to oppose an aspirated [p] to a non-aspirated one in

the same phonetic context to distinguish meanings. That is why aspiration

is a non -distinctive feature of English consonants.

1.1.3. Phonological and phonetic mistakes in pronunciation

As it has been mentioned above any change in the invariant ofthe pho­

neme affects the meaning. Naturally, anyone who studies a foreign language

makes mistakes in the articulation ofparticular sounds. L. V. Shcherba clas­

sifies the pronunciation errors as phonological and phonetic.

If an allophone of some phoneme is replaced by an allophone of a dif­

ferent phoneme the mistake is called phonological, because the meaning

of the word is inevitably affected. It happens when one or more relevant

features of the phoneme are not realized:

When the vowel [i:] in the word beat becomes slightly more open, more

advanced or is no longer diphthongized the word beat may be perceived as

quite a different word bit. It is perfectly clear that this type of mistakes is

not admitted in teaching pronunciation to any type of language learner.

If an allophone of the phoneme is replaced by another allophone of

the phoneme the mistake is called phonetic. It happens when the invari­

ant ofthe phoneme is not modified and consequently the meaning of the

word is not affected, e. g. :

When the vowel [i:] is fully long in such a word as sheep, for instance,

the quality of it remaining the same, the meaning of the word does not

change. Nevertheless language learners are not to let phonetic mistakes

into their pronunciation. If they do make them the degree of their foreign

accent will certainly be an obstacle to the listener's perception and under­

standing.

24

Chapter I. The Functional Aspect of Speech Sounds

1.2. Transcription

It is interesting at this stage to consider the system ofphonetic notations

which is generally termed "transcription". Transcription is a set of symbols

representing speech sounds. The symbolization of sounds naturally differs

according to whether the aim is to indicate the phoneme, i. e. a functional

unit as a whole, or to reflect the modifications of its allophones as well.

The International Phonetic Association (IPA) has given an accepted

inventory of symbols, used in different types of transcription.

The first type ofnotation, the broad or phonemic transcription, provides

special symbols for all the phonemes of a language. The second type, the

narrow or allophonic transcription, suggests special symbols for speech

sounds, representing particular allophonic features. The broad transcrip­

tion is mainly used for practical purposes (in EFL teaching and learning, for

example), the narrow type serves the purposes of research work.

The striking difference among present -day broad transcriptions of Brit­

ish English is mainly due to the varying significance which is attached to

vowel quality and quantity. Now we shall discuss two kinds of broad tran­

scription which are used for practical purposes in our country. The first type

was introduced by D. Jones. He realized the difference in quality as well as

in quantity between the vowel sounds in the words sit and seat, pot and port,

pull and pool, the neutral vowel and the vowel in the word earn. However, he

aimed at reducing the number of symbols to a minimum and strongly in­

sisted that certain conventions should be stated once for all. One of these

conventions is, for instance, that the above-mentioned long and short vow­

els differ in quality as well as in quantity. D. Jones supposed that this con­

vention would relieve us from the necessity of introducing special symbols

to differentiate the quality of these vowels. That is why he used the same

symbols for them. According to D. Jones' notation English vowels are de­

noted like this: [I] - [i:], [e] - [ee], [A] - [a:], [J] - [J:], [u] - [u:], [a] - [a:].

This way of notation disguises the qualitative difference between the vowels

[I] and [i:], [J] and [J:], [u] and [u:], [a] and [a:] though nowadays most pho­

neticians agree that vowel length is not a distinctive feature ofthe vowel, but

is rather dependent upon the phonetic context, i. e. it is definitely redun­

dant. For example, in such word pairs as hit - heat, cock - cork, pull- pool

the opposed vowels are approximately of the same length, the only differ­

ence between them lies in their quality which is therefore relevant.

More than that. Phonetic transcription is a good basis for teaching the

pronunciation ofa foreign language, being a powerful visual aid. To achieve

1.3. Main Trends in the Phoneme Theory

25

good results it is necessary that the learners of English should associate each

relevant difference between the phonemes with special symbols, i. e. each

phoneme should have a special symbol. If not, the difference between the

pairs of sounds above may be wrongly associated with vowel length which is

non-distinctive (redundant) in modern English.

The other type ofbroad transcription, first used by V. A. Vasilyev, causes

no phonological misunderstanding providing special symbols for all vowel

phonemes: [I], [i:], [e], [ee], [a:], [A], [n], [J:], [u], [u:], [3:], [a]. Being a good

visual aid this way of notation can be strongly recommended for teaching

the pronunciation of English to any audience.

But phonemic representation is rather imprecise as it gives too little

information about the actual speech sounds. It incorporates only as much

phonetic information as it is necessary to distinguish the functioning of

sounds in a language. The narrow or phonetic transcription incorporates

as much phonetic information as the phonetician desires, or as he can

distinguish. It provides special symbols to denote not only the phoneme as

a language unit but also its allophonic modifications. The symbol [h] for

instance indicates aspirated articulation, cf. [k(h)eIt] - [skeIt]. This type

of transcription is mainly used in research work. Sometimes, however, it

may be helpful, at least in the early stages, to include symbols representing

allophones in order to emphasize a particular feature of an allophonic

modification, e. g. in the pronunciation of the consonant [1] it is often

necessary to insist upon the soft and hard varieties of it ("clear" and

"dark" variants) by using not only [1] but also [1] (the indication of the

"dark" variant).

1.3. Main Trends in the Phoneme Theory

Now that we have established what the phoneme is, le.t us view the main

trends ofthe phoneme theory. Most linguists agree that the phoneme serves

to distinguish morphemes and words thus being a functional unit. However,

some ofthem define it in purely "psychological" terms, others prefer phys­

ically grounded defmitions. Some scholars take into consideration only the

abstract aspect ofthe phoneme, others stick only to its materiality. This has

divided various "schools" of phonology some of which will be discussed

below. Views of the phoneme seem to fall into four main classes.

As you see from the definition of the phoneme suggested above the au­

thors ofthe book share L. V. Shcherba's view, because it is obviously impor­

26

Chapter 1. The Functional Aspect of Speech Sounds

tant to look upon the phoneme as a unity of its three aspects: material, ab­

stract and functional.

The "mentalistic" or "psychological" view regards the phoneme as an

ideal "mental image" or a target at which the speaker aims. Actually pro­

nounced speech sounds are imperfect realizations of the phoneme existing

in the mind but not in the reality. Allophones of the same phoneme cannot

be alike because of the influence of the phonetic context.

According to this conception allophones of the phoneme are varying

materializations of it. This view was originated by the founder of the pho­

neme theory, the Russian linguist I. A. Baudauin de Courtenay. Similar

ideas were expressed by E. D. Sapir. This point of view was shared by other

linguists, A. Sommerfelt (Sommerfelt 1936) for one, who described pho­

nemes as "models which speakers seek to reproduce".

The "psychological", or "mentalistic" view ofthe phoneme was brought

back into favour by generative phonology, and the idea of the phoneme as a

"target" was revived, albeit under different terminology by N. Chomsky

Chomsky, M. Halle, 1968), M. Tatham (Tatham 1980) and others. Now

the basic concepts ofgenerative phonology attract much attention because

of the rapid development of applied linguistics.

The so-called "functional" view regards the phoneme as the minimal

sound unit by which meanings may be differentiated without much regard

to actually pronounced speech sounds. Meaning differentiation is taken to

be a deftning characteristic of phonemes. Thus the absence of palatalization

in [I] and palatalization of [1] in English do not differentiate meanings, and

therefore [I] and [1] cannot be assigned to different phonemes but both form

allophones of the phoneme [1]. The same articulatory features of the Rus­

sian [n] and [n'] do differentiate meanings, and hence [JI] and [JI'] must be

assigned to different phonemes in Russian, cf. MOA MOAb, A02 - /lif2. Ac­

cording to this conception the phoneme is not a family of sounds, since in

every sound only.a certain number of the articulatory features, i. e. those

which form the invariant of the phoneme, are involved in the differentiation

of meanings. It is the so-called distinctive features of the sound which make

up the phoneme corresponding to it. For example, every sound of the Eng­

lish word ladder includes the phonetic feature oflenisness but this feature is

distinctive only in the third sound [d], its absence here would give rise to a

different word latter, whereas if any other sound becomes fortis the result is

merely a peculiar version of ladder. The distinctiveness of such a feature

thus depends on the contrast between it and other possible features belong­

ing to the same set, i. e. the state of the vocal cords. Thus when the above­

.3. Main Trends in the Phoneme Theory

27

mentioned features are distinctive, lenisness contrasts with fortisness. Some

approaches have taken these oppositions as the basic elements of phono­

logical structure rather than the phonemes in the way the phoneme was

deftned above. The functional approach extracts non-distinctive features

from the phonemes thus divorcing the phoneme from actually pronounced

speech sounds. This view is shared by many foreign linguists. See in particu­

lar the works ofN. Trubetskoy (1960), L. BloomfIeld (1933), R. Jakobson,

M. Halle (1956), who deftne the phoneme as a bundle of distinctive fea­

tures.

The functional view of the phoneme gave rise to a branch oflinguistics

called "phonology" or "phonemics" which is concerned with relationships

between contrasting sounds in a language. Its special interest lies in estab­

lishing the system of distinctive features of the language concerned. Pho­

netics is limited in this case to the precise description of acoustic and psy­

chological aspects ofphysical sounds without any concern to their linguistic

function. The supporters of this conception even recommend to extract

phonetics from linguistic disciplines which certainly cannot be accepted by

Russian phoneticians.

A stronger form of the "functional" approach is advocated in the so­

called "abstract" view of the phoneme, which regards phonemes as essen­

tially independent of the acoustic and physiological properties associated

with them, i. e. of speech sounds. This view ofthe phoneme was pioneered

by L. Hjelmslev (1963) and his associates in the Copenhagen Linguistic

Circle, H. 1. Uldall and K. Togby.

The views of the phoneme discussed above regard the phoneme as an

abstract concept existing in the mind but not in the reality, i. e. in human

speech, speech sounds being only phonetic manifestations of these con­

cepts.

The "physical" view regards the phoneme as a "family" of related

sounds satisfYing certain conditions:

1. The various members of the "family" must show phonetic similarity

to one another, in other words be related in character.

2. No member of the "family" may occur in the same phonetic context

as any other.

The extreme form ofthe "physical" conception as suggested by D. Jones

(1967) excludes all reference to non-articulatory criteria in the grouping of

sounds into phonemes. And yet it is not easy to see how sounds could be as­

signed to the same phoneme on any other grounds than that substitution of

one sound for the other does not give rise to different words and different

Chapter L The Functional Aspect of Speech Sounds

28

meaning. The representatives ofthis approach view the phoneme as a group

of similar sounds without any regard to its functional and abstract aspects.

Summarizing we may state that the conception ofthe phoneme first put

forward by L. V. Shcherba may be regarded as the most suitable for the pur­

pose of teaching.

1.4. Methods of Phonological Analysis

1.4.1.

The aim of phonological analysis

Now that you have a good idea of what a phoneme is, we shall try to

establish the aim of phonological analysis ofspeech sounds, to give an over­

view of the methods applied in this sort of analysis and show what charac­

teristics ofthe quality ofsounds are ofprimary importance in grouping them

into functionally similar classes, i. e. phonemes.

To study the sounds of a language from the functional point of view

means to study the way they function, that is to find out which sounds a

language uses as part of its pronunciation system, how sounds are grouped

into functionally similar units. The final aim of phonological analysis of a

language is the identification of the phonemes and finding out the patterns

of relationships into which they fall as parts of the sound system ofthat lan­

guage.

There are two ways of analyzing speech sounds: if we define /s/ from the

phonological point of view it would be constrictive foreliIlb'1lal fortis, this

would be quite enough to remind us of the general class of realization ofthis

segment; for articulatory description we would need much more informa­

tion, that is: what sort of narrowing is formed by the tip of the tongue and

the alveolar ridge, what is the shape of the tongue when the obstruction is

made (a groove in the centre of the tongue while the sides form a closure

with the alveolar ridge), and so on. So if the speech sounds are studied from

the articulatory point of view it is the differences and similarities of their

production that are in the focus of attention, whereas the phonological ap­

proach suggests studying the sound system which is actually a set of rela­

tionships and oppositions which have functional

Each language has its own system of phonemes. Each member of the

system is determined by all the other members and does not exist without

them. The linguistic value of articulatory and acoustic qualities of sounds is

not identical in different languages. In one language community two physi­

104. Methods of Phonological Analysis

29

cally different units are identified as "the same" sound, because they have

similar functions in the language system. In another language community

they may be classified as different because they perrorm a distinctive func­

tion. Consider the following comparison: the two English [1] and·[l] sounds

(clear and dark) are identified by English people as one phoneme because

the articulatory difference does not affect the meaning. English speakers are

not aware of the difference because it is of no importance in the communi­

cation process.

In the Russian language a similar, though not identical difference be­

tween [JI] and [JI'] affects the meaning, like inAYK andAlOK. So these sounds

are identified by Russian speakers as two different phonemes. Analogically,

the speakers of Syrian notice the difference between the [th] of English ten

and the [t] of letter, because it is phonemic in Syrian but only allophonic in

English.

Thus a very important conclusion follows: statements concerning pho­

nological categories and allophonic variants can usually be made of a par­

ticular language.

So the aim of the phonological analysis is, firstly, to determine which dif­

ferences of sounds are phonemic and which are non-phonemic and, sec­

ondly, to find the inventory of the phonemes of a language.

1.4.2. Distributional method of phonological analysis

There are two most widely used methods of finding out what sounds are

contrastive. They are the formally distributional method and the semanti­

cally distributional method.

The formally distributional method consists in grouping all the sounds

pronounced by native speakers into phonemes according to the two laws of

phonemic and allophonic distribution. The laws were discovered long ago

and are as follows:

1. Allophones of different phonemes occur in the same phonetic con­

text.

2. Allophones of the same phoneme never occur in the same phonetic

context.

The sounds of a laIlb'1lage combine according to a certain pattern charac­

teristic of this language. Phonemic opposability depends on the way the pho­

nemes are distributed in their occurrence. That means that in any language

certain sounds do not occur in certain positions, like [h] never occurs word

finally while [D] never occurs word initially. Such characteristics permit iden­

30

L The Functional Aspect of Speech Sounds

tification of phonemes on the grounds of their distribution. Ifa sound occurs

in a certain phonetic context and another one occurs in a different phonetic

context no two words of a language can be distinguished solely by means of

the opposition between those two. The two sets ofphonetic contexts are com­

plementing each other and the two sounds are classed as allophones of the

same phoneme. They are said to be in complementary distribution. Consider

the following: ifwe fully palatalize [I] in the word "let" it may sound peculiar

to native speakers but the word is still recognized as "let" but not "bet" or

"pet". The allophones lack distinctive power because they never occur in the

same phonetic context and the difference in their articulation depends on dif­

ferent phonetic environment. To be able to distinguish the meaning the same

sounds must be capable ofoccuqing in exactly the same environment like [p]

and [b] in "pit" and "bit". Thus two conclusions follow:

I. If more or less diflerent sounds occur in the same phonetic context

they should be allophones of different phonemes. In this case their distribu­

tion is contrastive.

2. If more or less similar sounds occur in different positions and never

occur in the same phonetic context they are allophones ofone and the same

phoneme. In this case their distribution is complementary.

There are cases when allophones are in complementary distribution

are not referred to the same phoneme. This is the case with the English

me­

and [lJ]: [h) occurs only initially or before a

distribution is mod­

dially or finally after a voweL In this case

similarity/dissimilarity. Articu­

ified by addition ofthe criterion

latory features are taken into account.

So far we have considered cases when the distribution of sounds was

or complementary. There is a third possibility, namely,

sounds occur in the language but the speakers are inconsistent in

the way they use them, like in the case ofthe Russian KGflOlUU - ZGflOlUU. In

such cases we must take them as free variants ofa single phoneme. The rea­

son for the variation in the realization of the same phoneme could be ac­

counted for by dialect or other social factors ..

1.4.3. Semantically distributional method of phonological analysis

There is another method of phonological analysis widely used in Rus­

sian linguistics. It is called the semantically distributional method or seman­

tic method. It is applied for phonological analysis of both unknown lan­

guages and languages already described. The method is based on a phonemic

1.4. Methods of Phonological Analysis

31

rule that phonemes can distinguish words and morphemes when opposed to

one another. The semantic method of identifying the phonemes of a lan­

guage attaches great significance to meaning. It consists in systemic substi­

tution of the sound for another in order to ascertain in which cases where

the phonetic context remains the same such substitution leads to a change

of meaning. It is with the help ofthe informant that the change of meaning

is stated. This procedure is called the commutation test. It consists in find­

ing minimal pairs of words and their grammatical forms. By a minimal pair

we mean a pair ofwords or morphemes which are differentiated by only one

phoneme in the same phonetic context.

Let's consider the following example: suppose the scholar arrives at the

sequence [pin]; he substitutes the sound [p] for the sound [b]. The substitu­

tion leads to the change of meaning. This proves that [p] and rbl can be re­

garded as allophones of different phonemes.

Minimal pairs are useful for establishing the phonemes

If we continue to substitute [p] for [8], [d], [w] we get minimal pairs of

words with different meaning sin, din, win. So [8], [d], [w] are allophones of

different phonemes. But suppose we substitute [ph] for [p], the pronuncia­

word would be wrong from the point ofview of English pronun­

ciation norm, but the word would be still recognized as pin but not anything

else. So we may conclude that the unaspirated [p] is an allophone of the

same

The phonemes ofa language form a system ofoppositions in which any

phoneme is usually opposed to other phonemes of the language in at least

one position, in at least one minimal pair. So to establish the phonemic

structure of a language it is necessary to establish the whole system of op­

positions. AU the sounds should be opposed in word-initial, word-medial

and word-final positions. There are three kinds of oppositions. If members

ofthe opposition differ in one feature the opposition is said to be single, like

in pen - ben. Common features: occlusive, labiaL Differentiating feature:

fortis -lenis. Iftwo distinctive features are marked the opposition is said to

be double, like in pen den. Common feature: occlusive. Differentiating

features: labial - lingual, fortis voiceless - lenis voiced. If three distinctive

features are marked the opposition is said to be triple (multiple), like in

pen - then. Ditlerentiating features: occlusive constrictive, labial - den­

tal, fortis voiceless lenis voiced.

The features ofa phoneme that are capable of differentiating the mean­

ing are termed as relevant or distinctive. The ones that do not take part in

differentiating the meaning are termed as irrelevant or non-distinctive. The

32

Chapter 1. The Functional A~pect of Speech Sounds

latter can be oftwo kinds: a) incidental or redundant features like aspiration

ofvoiceless plosives, presence ofvoice in voiced consonants, length ofvow­

els; b) indispensable or concomitant features like tenseness of English long

monophthongs, the checked character of stressed short vowels, lip round­

ing of back vowels.

So the phonological analysis of the sounds of a language is based on

such notions as contrastive distribution, minimal pairs, free variation. To

this we must add one more concept, native speaker's knowledge. All the

rules referred to above should account for the intuition of the native speaker