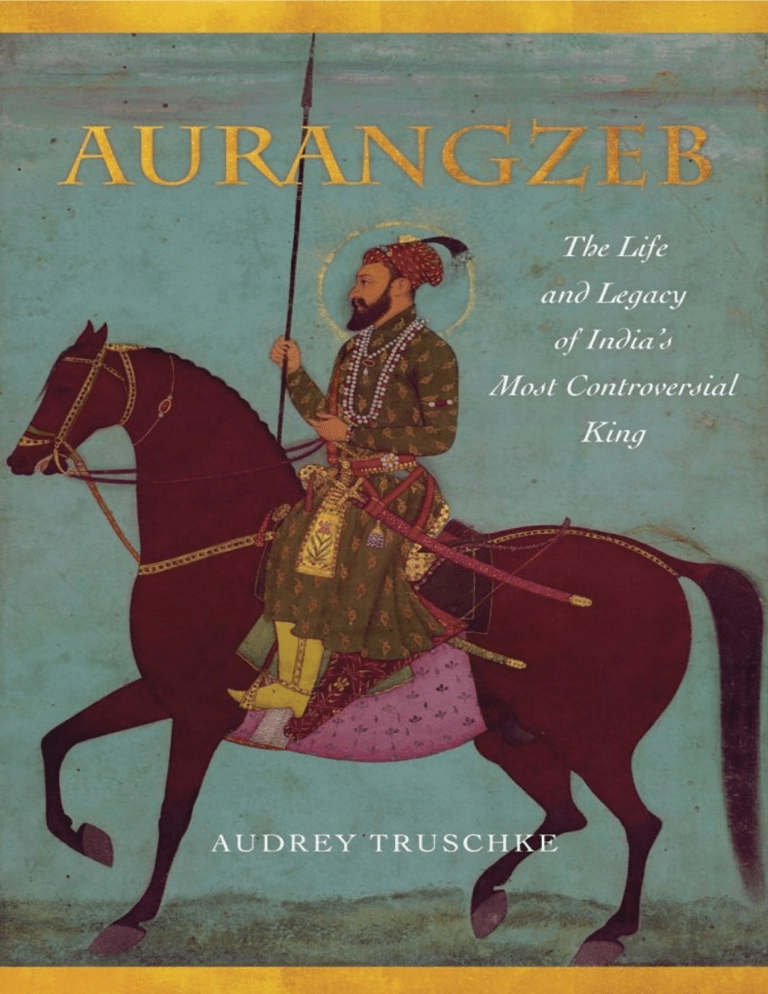

Aurangzeb The Life and Legacy of India’s Most Controversial King ( PDFDrive )

реклама