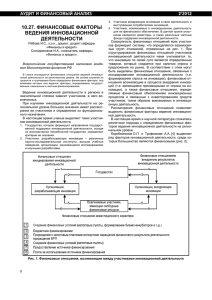

Инновации, имитации и рост Александр Тонис, РЭШ, Москва

реклама

Инновации, имитации и рост Александр Тонис, РЭШ, Москва Эволюция распределения стран по уровню развития 2 Чем объяснить отсутствие сходимости? • Неоклассические модели роста не дают объяснения: по накапливаемым факторам есть тенденция к сближению, а по TFP – нет (Easterly and Levine, 2000; Feyrer, 2003) • Современные модели роста: эндогенный рост, шумпетерианская концепция созидательного разрушения. 3 Шумпетерианская динамика (Aghion and Howitt, 1988,1998) • y(x) = Axα , x + n = L (x – фактор пр-ва, n – исследования) • Пуассоновский поток новых технологий (At+1 = γAt); интенсивность их создания: λn • Автор новой технологии становится монополистом (до прихода следующей) – созид. разрушение • Ожидаемый выигрыш монополиста: Vt+1 = πt+1 dτ + (1 – λn t+1 dτ) e – r dτ Vt+1 => Vt+1 = πt+1 / (r + λn t+1) • Монопольная прибыль: πt = max xt (y' (xt) – wt+1) xt => xt = (α2At / wt)1/(1 – α) ; πt = (1/ α – 1)wt xt • Безразличие при выборе между работой на производстве и в исследованиях: wt = y'(x) = λV t+1 4 Равновесие и общ. оптимум • Стационарное равновесие (n = const): 1 = λ γ (1/ α – 1) (L – n) / (r + λn) • Максимум обществ. благосостояния W = A0 (L – n)α dτ + (1 – λn dτ) e –r dτ W + λn dτ e –r dτ γW W = A0 (L – n)α / (r – λ n (γ – 1)) → maxn 1 = λ (γ – 1) (1/α) (L – n) / (r – λ n (γ – 1)) • + стимул к инновациям – автор инновации присваивает лишь часть общественного выигрыша (монополия + неучет межвременных экстерналий – business stealing) • Целесообразно ли распространение технологий?5 Инновации и имитации • Долгосрочный рост основан на инновациях и имитациях • Концепция “преимущества отсталости” (Gerschenkron, 1962). • Догоняющее развитие: – заимствование технологий – крупные инвестиции – “неконкурентные” решения: крупные компании, долгосрочные соглашения между компаниями и банками (и интегрированные структуры), вмешательство государства (пром. политика) • Имитации дешевле инноваций => сходимость (Barro and Sala-i-Martin, 1995). 6 Инновации и имитации на разных стадиях развития • Развитые страны совершают инновации; развивающиеся – заимствуют: – отбор менеджеров по способности к инновациям или инвестициям (Acemoglu et al, 2006) – вертикальная интеграция или малые инновационные фирмы (Acemoglu et al, 2003) – технологические и институциональные барьеры, препятствующие инновациям (Howitt and MayerFoulkes, 2002) • Темп роста зависит от положения среди остальных => сложная динамика (Полтерович, Хенкин, 1998, 1999) 7 Инновации, имитации и отбор менеджеров (Acemoglu et al, 2006) • Основная идея: – развивающиеся страны растут за счет заимствования технологий и инвестиций; компании стремятся к долгосрочному найму менеджеров, способных реинвестировать накопленный капитал в крупные проекты; – развитые страны растут за счет инноваций; компании стремятся к найму талантливых менеджеров, способных к инновациям, и готовы для этого пожертвовать расширением производства. 8 Модель: структура производства • Конкурентное производство конечного продукта из высокотехнологичных “промежуточных товаров” yt 1 N 1 t 1 A 1 xt d 0 • Монополистическое производство каждого из промежуточных товаров из конечного продукта: из единицы yt – единица xt(ν) πt(ν) = (pt(ν) – 1) xt(ν) → max s. t. pt(ν) ≤ χ => πt(ν) = δ(χ)At(ν) Nt, δ(χ) = (χ – 1) χ – 1(1 – α) ↑ χ 9 t Модель: имитации и инновации • Эволюция технологий в отрасли ν : At(ν) = st(ν) (ηĀt – 1 + γt(ν) At – 1), где At – 1 – средний уровень At – 1(ν); Āt – 1 – максимальный среди всех стран уровень At – 1 (мировая технологическая граница); Āt = (1 + g)Āt – 1 st(ν) = 1 или st(ν) = σ < 1 – масштаб модернизации (размер проекта); γt(ν) = 0 или γt(ν) = γ > 0 – инновационные способности менеджера 10 Инновации, имитации и стратегия отбора • Модель с перекрывающимися поколениями: участники живут два периода • Менеджер, выполнивший проект, получает долю μ его прибыли. • Ценность “молодых” менеджеров – только в том, что среди них есть талантливые • Ценность “опытных” менеджеров – еще и в том, что они могут реинвестировать свой капитал в крупный проект (несовершенство рынка капитала: взятие кредита извне невозможно) • Trade-off: уволить неспособного к инновациям опытного менеджера или оставить? 11 Имитации и инновации: стратегия фирмы • Эволюция технологий: At(ν) = st(ν) (ηĀt – 1 + γt(ν) At – 1) • На ранних стадиях развития выгодно оставить опытного менеджера; ближе к “переднему краю” выгодно нанять нового b c • Пороговое значение a = A / Ā : ar , 1 1 a < ar(μ,δ) => оставить; a > ar(μ, δ) => уволить; ar(μ, δ) ↑ δ (чем сильнее конкуренция, тем скорее переход к инновационной стратегии) ar(μ, δ) ↑ μ при слабой конкуренции (большом δ); ar(μ, δ) ↓ μ при сильной конкуренции (малом δ) 12 Равновесие, макс. рост и ловушка экстенсивного развития 13 Недостатки модели Acemoglu et al. (2006) • Заимствуется самая передовая технология – не реалистично: в слаборазвитых странах заимствование имеет мало шансов на успех • Мотивация выбора между имитациями и инновациями довольно специфическая (объяснение “пожизненного найма” в Японии) • Не отражено должным образом накопление капитала 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Evolution of distance to frontier and capital • Assume that TFP of the most developed country increases with a constant growth rate.gEvolution of a and k: 1 a1 a, 1 g 1 f ( x) (1 )k k1 (1 g ) 1 22 23 24 25 Abs.Capacity – Introduction • The concept of absorptive capacity has been originally introduced as a characteristic of a firm, namely its "ability to recognize the value of new, external information, assimilate it, and apply it to commercial ends" (Cohen, Levinthal, 1990). Later on, this concept was applied to a country as a whole. • L. Suarez-Villa in 1990: a concept of innovative capability: the ability of a country – as both a political and economic entity – to produce and commercialize a flow of innovative technology over the long term». Furman, Porter, Stern (2002, p.1). 26 Abs.Capacity – Introduction • Possibilities to arrange good policies depend on our knowledge of absorptive and innovative capacities as well as on factors which influence both quantities. However, the task to separate and measure two abilities is not trivial. Instead, a number of researches try to suggest indicators that characterize technological capabilities of countries. • In Archibugi , Coco (2005), authors describe and compare five indicators developed by different organizations. • All of them are based on a set of country characteristics and on “arbitrary weighting schemes with limited theoretical or empirical bases” (World Bank, 2008). 27 Abs.Capacity – Introduction • In UNIDO (2005), weights were chosen by factor analysis that was carried out on 29 indicators, and five principal factors were labeled as knowledge, inward openness, financial system, governance, and the political system. • A similar methodology has been used in World Bank (2008). As much as 34 variables were used over the 1990–2006 period. To calculate overall index of technological absorptive capacity four types of characteristics were taken into account: Macroeconomic environment; Financial structure and intermediation; Human capital, Governance. • Dutta, S. and I. Mia in their Global Information Technology Report (2009) suggested two indexes based on surveys: CI (Capacity for innovation) and FA (Firmlevel technology absorption). 28 Importance • “Both policy analysts and academic researchers need new and improved measures of technological capabilities on the performance of nations to understand economic and social transformations. With regard to policy analysis, this has relevance for public and business practitioners. Governments constantly require information about the performance of their own country, and this is often better understood in comparison to the performance of their partners and competitors” (Archibugi and Coco , 2005, pp.175-176). • Up to now there is neither general strict definition of absorptive capacity nor convincing methodology to measure it. This paper tries to fill in this gap. 29 In this paper • We try to build indicators that could not only serve for comparisons of different countries technology levels but also could help to choose most efficient direction to invest. • New definitions of absorptive capacity and innovative capability • An approach to measure them 1)based on Schumpeterian-type model (Acemoglu, Aghion and Zilibotti, (200) ; 2) combines calibration and econometric approach; 3) included analyses of both indicators on characteristics of countries. • Poltrovich, Tonis (2003, 2005), Piklina (MT, 2009) 30 New Definitions • The absorptive capacity is defined as the cost of 1% TFP increase of a country's capital unit through technology imitation of other economies. • Analogously, the innovative capability is defined as the cost of 1% TFP increase of a country's capital unit through technology innovations. • Technology is understood in a broad sense as a method of production, trade, governance, etc. 31 Hypotheses • 1) Absorptive capacity is negatively correlated with relative level of development; the higher is this level the larger is innovative capacity. Barro and Sala-IMartin (1995) Acemoglu, Aghion and Zilibotti (2002). • 2) International trade positively influences absorptive capacity. • 3) Human capital has positive impact on innovative capability. Acemoglu, Aghion, Zilibotti (2003, 2006), Vandenbussche, Aghion, Meghir (2004), Rogers (2004). • 4) Institutional quality positively influences both absorptive and innovative capacities. • 5) Banking system is more important for imitation whereas financial markets play decisive role for innovative development. Chakraborty, Ra (2006), 32 Deidda, Fattouh (2008)). Absorptive and innovative capacities • ci , i =1,2 may be calculated as c1= q1b1 , c2= q2b2 where projects b1 , b2 each gives 1% increase of TFP productivity of a capital unit. • This means • b1ψ1( b1)=0.01, • b2ψ2( b2)=0.01. • Therefore, ci 0.01i qi / ( i 0.01), i 1, 2 33 Modification 1: human capital provided by the state • Assume that output Y of the final good is taxed to finance education sector: • τ(a) - education tax rate depending on a. • q1 (a, H, S), q2 (a, H, S), H –human capital. Evolution of capital : (1 (a )) f ( x ) (1 K )k k1 (1 g ) 1 N 1 H 1 (1 H ) NH m(a ) (a)Y where δH is the human capital depreciation rate (0 ≤ δH ≤ 1), m(a) is a multiplier measuring the impact of education on human capital. 34 Modification 2: human capital provided by firms • Suggested by Pikulina (2009) in her Master Thesis at NES. • Human capital is financed by firms directly, as a result of their optimal choice • Firm’s cost of providing Hv units of human capital (under average human capital H): 35 Methodology of calibration-1 • Calibration involves estimating the following parameters: • α –parameter of the Cobb-Douglas production function; • μ1– maximal growth rate due to imitation; • μ2 – maximal growth rate due to innovation; • ρ – technology obsolescence rate; • λ – adjustment ratio used for estimating the share of innovation and imitation in TFP growth (see below); • β – parameters of cost functions qi (see below). 36 Methodology of calibration-2 • y-relative per capita GDP - ratio of country’s per capita GDP to ŷthat of the USA. • Start from y1981, the relative per capita GDP in 1981 (corresponding to the earliest period 1980-1982 in our data series) and, using the model, try to predict , the relative per capita GDP in 2005 (corresponding to the latest period 2004-2006). • Criterion: the sum of squares of logarithmic errors E ln( yˆ 2005 ) ln( y2005 ) min 2 yˆ actual , y predicted 37 Methodology of calibration-3 • • 1. 2. 3. 4. Combination of calibration and regressions Four steps: Estimate α, the parameter of the Cobb-Douglas production function, from the standard growth regression and calculate TFP. Fix parameters μ1, μ2, ρ, λ, calculate q1 ,q2 from the model, and estimate two linear regressions with dependent variables q1 ,q2 as functions of a, S (coefficients β). Using this functions, find optimal values of μ1, μ2, ρ, λ. Go to the Step 2, or finish if criterion improvement is small enough. 38 Methodology of calibration-4 Decomposition of the calibration problem • simplifies the process of calibration • allows estimation of statistical significance of factors contributing to the absorptive and innovative capacities. • A seeming disadvantage: the result is not an exact solution to the calibration problem. • In fact, we restrict our opportunities for adjustment getting in return for an opportunity to interpret key results at intermediate stages, and, in the case of success, to get higher confidence that the success is not occasional. 39 Methodology of calibration-5 • • Important hypothesis: ratio of rates of growth induced by innovations and imitations is proportional to royalty receipts over royalty payments. We have no microfoundations behind this hypothesis. Implicitly, it describes a mechanism by which domestic knowledge, embodied into royalty receipts, and foreign knowledge, embodied into royalty payments, both influence domestic rate of growth. 40 Data • World Development Indicators (WDI, 2008), International Country Risk Guide (ICRG, 2004), physical capital stock dataset (Nehru and Dhareshwar, 1993), Barro-Lee dataset on human capital. • Y– GDP, years 1980-2006; N– population; I – gross fixed capital formation; K – capital stock; R– ICRG composite risk index, is higher for lower risks; LB– royalty payments, total value of licenses boughtI; LS– royalty receipts, total value of licenses sold; T– manufactures trade (export+import) ; B – domestic credit provided by banking sector; F – foreign direct investment; P – the number of scientific publications per 1000 people; H– total years of schooling (age 15+), measure of human capital stock, ED – public spendings on education. Data is averaged by 9 three-year periods • • • • • • • • • • 41 Accessorial variables 42 Regressions for H , R, B • H = 7.940***a + 3.479*** • R = 40.08***a + 53.52*** • B = 1.213***a + 0.0235***I + 2.140*** 43 Model with exogenous human capital: parameters calibrated 44 Model with exogenous human capital: estimated imitation cost function. 45 Model with exogenous human capital: estimated innovation cost function. 46 Model with exogenous human capital:results-1 • The results confirm, at least partially, our main hypotheses about the absorptive capacity and innovative capability. • More developed countries have higher innovation capacity and lower absorptive capacity. For poor countries, both indicators are less sensitive to changes of the distance to the frontier than for rich ones. • Human capital enhances the innovative capability and does not affect significantly the absorptive capacity. This does not contradict our hypothesis that imitation is less sensitive to educational level. However, it may happen that another indicator – literacy rate – could be more appropriate for this case. Unfortunately, we have data on literacy rates for short period of time only. 47 Model with exogenous human capital:results-2 • Institutional quality improves both absorptive capacity and innovative capability. • Absorptive capacity is positively affected by the international trade. Its correlation with innovative capability is negative, the fact for which we have not any clear explanation. • FDI contribution into both abilities is insignificant. This does not contradict to the observation that FDI influence on rate of growth is mixed. • Number of scientific publications is positively related to the innovative capability. 48 Regression 49 Regression 50 Distribution of ln(y), 1981 51 Distribution of ln(y), 2005 52 Regressions for m and τ 53 m(a) = efficiency of education spendings 54 τ(a) = education spendings GDP 55 increment of human capital m(a)τ(a) = GDP 56 Model with endogenous human capital: parameters calibrated 57 Model with endogenous human capital: regression for q1 Model with endogenous human capital: regression for q2 Results • Comparing these results to the results of calibrating the basic model shows that the way of computing human capital does not matter: all the qualitative implications are the same. • The accuracy of the calibration has become slightly better (standard error 0.0857 versus 0.0881). So, the human capital data implied from the data on the education spending is slightly better predictor than the data based on the schooling years only. 60 Absorptive capacities and innovative capabilities 61 Absorptive capacities and innovative capabilities 62 Relation to other measures of technological capabilities-1 • Dutta, S. and I. Mia (eds) (2009). The Global Information Technology Report 2008–2009. • Two indexes based on surveys: - CI: Capacity for innovation (1 = companies obtain technologies exclusively from licensing or imitating foreign companies, 7 = by conducting formal research and pioneering their own new products and processes). - FA: Firm-level technology absorption (1 = companies are not able to absorb new technology, 7= companies are aggressive in 63 absorbing new technology); CI and our measures of absorptive and innovative capacities 64 FA and our measures of absorptive and innovative capacities 65 Relation to other measures of technological capabilities • Archibugi, D. and A. Coco (2005). Measuring technological capabilities at the country level: A survey and a menu for choice. • Five technology indexes (WEF, UNDP, ArCo, UNIDO, RAND), each including innovation, infrastructure, technology diffusion, human capital, competitiveness. For each of them, countries are ranked. • TR: mean rank of WEF, UNDP, ArCo, and RAND. 66 Relation to other measures of technological capabilities – conclusion • These indexes capture innovation capability rather than absorption capacity. In particular, FA refers to firms’ ability to absorb any new technologies rather than imitated ones. • Probably, these indexes do not take into account high imitation costs in technologically advanced countries. • Our indexes of absorptive capacities and innovative capabilities take into account these factors. 67 Conclusions • We develop an approach to the estimation of country absorptive capacities and innovative capabilities. • New more precise definitions. • The method of calculation uses a simple dynamic model and combines calibration and econometric approaches. This gives a possibility to analyze how calculated indicators depend on different factors. 68 Conclusions • The model predicts main feature of the real evolution of countries distribution by GDP per capita. • The estimations are conducted not for each country separately but for a group of economies jointly. This gives us additional information which is not contained in data on a country alone. There are a lot of possibilities to improve our approach. • OLG model instead of one period model. • Include labor markets with workers of different qualifications • Include sectors of education and research. • To try different hypotheses to reach the separation of imitation and innovation costs and results. 69