Валентин Серов. Линия жизни - The Tretyakov Gallery Magazine

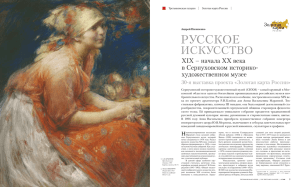

реклама

ТРЕТЬЯКОВСКАЯ ГАЛЕРЕЯ ВЫСТАВКИ Мария Иванова Валентин Серов. Линия жизни Валентин Александрович Серов (1865–1911) – ключевая фигура в русском искусстве рубежа XIX–XX веков. Широкой публике он известен, в первую очередь, как живописец, но уже современники ценили в нем талант графика. «Серов-рисовальщик, быть может, даже сильнее Серова-живописца», – писал И.Э. Грабарь. Выставка «Валентин Серов. Линия жизни», проходящая в Третьяковской галерее с декабря 2011 по май 2012 года, предоставляет возможность проследить творческий путь мастера на примере коллекции его произведений из собрания отдела графики ГТГ, никогда ранее не экспонировавшихся в подобном объеме. мя Валентина Серова имеет особое значение для Третьяковской галереи. Художник был дружен с наследниками П.М. Третьякова, в 1899–1911 годах являлся членом Совета галереи, сделал многое для пополнения ее коллекции. Однако при жизни Серова музей обладал лишь немногими его работами. Будучи в составе руководства, Валентин Александрович не считал этичным приобретение для галереи собственных произведений. Основные поступления его работ происходили после 1911 года из семьи художника, Музея иконописи и живописи И.С. Остроухова, Цветковской галереи, Музея нового западного искусства и Государственного музейного фонда. Ныне Третьяковская галерея обладает наиболее полной и значительной коллекцией рисунков и акварелей мастера (более 750 отдельных листов, 45 альбомов). Многоплановость таланта Серова, широкий диапазон его творческих поисков, отражающих изменения, происходившие в искусстве Серебряного века, определили характер построения выставки. Экспозиция показывает динамику развития творчества художника, который наследует принципы реалистического искусства XIX века и предвосхищает открытия мастеров XX столетия. Наиболее ярко это развитие можно проследить на примере многочисленных портретов. Ранние работы (портреты Т.А. Мамонтовой, 1879; М.Я. Симонович, 1879) отличаются живописным подходом к рисунку, мягкостью карандашной моделировки и внимательным И Портрет балерины А.П. Павловой. 1909 Бумага, графитный карандаш 34,3 ¥ 21,3 Portrait of the Ballerina Anna Pavlova. 1909 Graphite pencil on paper 34.3 ¥ 21.3 cm 3Натурщица с распущенными волосами. 1899 Бумага, акварель, белила. 52,4 ¥ 35,5 3A Model with Loose Hair. 1899 Watercolour and white paint on paper 52.4 ¥ 35.5 cm ТРЕТЬЯКОВСКАЯ ГАЛЕРЕЯ / THE TRETYAKOV GALLERY / #1’2012 87 THE TRETYAKOV GALLERY CURRENT EXHIBITIONS CURRENT EXHIBITIONS Maria Ivanova Valentin Serov. The Line of Life Valentin Alexandrovich Serov (1865-1911) is a key figure in Russian art of the late-19th and early-20th centuries. The general public knows him first of all as a painter, although his graphic talent was appreciated even by his contemporaries. “Serov the graphic artist may be even more powerful than Serov the painter,” wrote Igor Grabar. The exhibition “Valentin Serov. The Line of Life,” on view at the Tretyakov Gallery from December 2011 until May 2012, traces the great artist’s trajectory through his works held at the Tretyakov Gallery’s graphic art department – many of which have not been publicly displayed before. У околицы Набросок. 1900-е Бумага, акварель, графитный карандаш 23,7 ¥ 33,5 Near a Fence Round a Village Croquis. 1900s Watercolour and graphite pencil on paper. 23.7 ¥ 33.5 cm alentin Serov is a special figure in the history of the Tretyakov Gallery. The artist was a friend of Pavel Tretyakov’s heirs, sat on the gallery’s board in 1899-1911, and did much to expand its collection. However, in Serov’s lifetime the museum held only a few of his works. As a member of the board, Serov considered it unethical for the gallery to buy his artwork. Most of his pieces were acquired by the museum after 1911, from the artist’s heirs as well as from the Ostroukhov Museum of Icons and Painting, the Tsvetkov Gallery, the Museum of New Western Art and the State Museum Fund. Today the Tretyakov Gallery has the most comprehensive and valuable collection of the artist’s graphic and watercolour pieces (more than 750 individual sheets, 45 albums). The diversity of Serov’s talent and his wide-ranging artistic explorations, which V 1 Valentin Serov. “Correspondence, Documents, Interviews. In two volumes”. Leningrad: 1989. (Hereinafter referred to as “Serov: Correspondence, Documents, Interviews”). Vol. 2. P. 151. 2 The painting of Titian, first held at the Hermitage and in 1931 sold to the USA, is now in possession of the National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.) 3 Valentin Serov. “Memoirs, Journals, Letters of His Contemporaries. In two volumes. Leningrad: 1971. (Hereinafter referred to as “Serov: Memoirs, Journals, Letters of His Contemporaries”). Vol. 2. P. 230. 88 ТРЕТЬЯКОВСКАЯ ГАЛЕРЕЯ / THE TRETYAKOV GALLERY / #1’2012 reflected the evolution of visual art in the “Silver Century”, are the core of the show’s conception. It reflects the dynamics of the evolution of the work of the artist who, while being an heir to the 19th-century realist tradition, anticipated the discoveries of 20th-century painters. This evolution can be traced particularly well through his numerous portraits. Serov’s earlier works (the portraits of Tatyana Mamontova (1879) and Maria Simonovich (1879)) are distinguished by their use of painterly techniques in drawing, the softness of their pencil modelling, and their faithfulness to nature. These pieces were apparently influenced by the work of Ilya Repin, from whom Serov took private lessons at the time. In 1880, despite his young age – he was not yet 16, the mandated admission age for the institution – Serov joined the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts and began to study in Pavel Chistyakov’s workshop. The academic style did not come naturally to the young artist accustomed to liberal brushwork in Repin’s vein, but Chistyakov immediately singled out his new student. Many years later, already a recognized artist, Serov confided to his mentor: “I remember you as the teacher and consider you the only (in Russia) true teacher of the eternal sacrosanct rules of forms – the only thing that can be taught…”1 When he studied under Chistyakov, Serov created a drawing depicting a sleeping Monsieur Tagnon (1884), a friend of the Mamontovs who had previously tutored their children. The principles set down by Chistyakov – careful study of nature, and learning from the great masters of the past – would forever remain pivotal to Serov’s artistic methods. He spent many hours at the Hermitage copying Rembrandt, Velázquez and Veronese. Often he would not slavishly copy the pieces but freely improvise on their themes. One such work is the watercolour “Venus at Her Mirror” (from the 1890s), a variation on the Titian painting2. From his student years onwards, sketching from nature was an important exercise through which Serov honed his graphic skills. His watercolour images of female sitters accomplished at the Moscow College of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture when he was already teaching there are of considerable value, and not just dry academic compositions. The Tretyakov Gallery’s collection boasts several images of “Serov’s favourite female sitter” (according to Mikhail Shemyakin), Vera Ivanovna3. The pieces vary in style depending on the artistic objective. One piece evokes the portraits of Henrietta Girshman (in the turn of В деревне. Баба с лошадью. 1898 Бумага, пастель 52 ¥ 69 In a Village. A Peasant Woman with a Horse 1898 Pastel on paper 52 ¥ 69 cm 4 Grabar, Igor. “Valentin Alexandrovich Serov: His Life and Art. 1865-1911”. Moscow: 1965. (Hereinafter referred to as “Grabar, 1965”.) P. 336. 5 Ibid., p. 174. 6 Grabar, Igor. “Serov”. Moscow: 1914. (Hereinafter referred to as “Grabar, 1914”). P. 82. the head, the puffy coiffure, and the elegant shoes), another is distinguished by economy of form and of the palette, bringing to mind the artist’s antiquity-themed pieces (“The Rape of Europa”, 1910). Until his last years Serov worked to improve his command of line and form by painting from nature. In 1910-1911 he attended the workshops of the Académie Julian and Académie Colarossi in Paris on equal terms with artists who were only beginning their careers. A rich experience in painting from nature and the ability to carry on through the long hours of anatomical drawing sessions were at the core of the craftsmanship of Serov the portraitist. In the 1900s Serov began to enjoy wide recognition and the resulting numerous portrait commissions. Always anxious to master new forms and style, the artist did not “waste” his talent working on an endless series of fashionable portraits. In each new work Serov set for himself a different goal, that of trying to capture the essence of his model’s character and to commit it to the canvas. Serov created a portrait of Sofia Lukomskaya, commissioned by the prominent industrialist Alexander Ratkov-Rozhnov, in 1900. “The image is so compelling,” wrote Igor Grabar, “that one of the most notable French psychiatrists, seeing a photograph of the watercolour, accurately diagnosed the mental state of the model, who by then had fallen prey to a serious disease.”4 Serov’s portraits were always distinguished by their insightful characterisation, sometimes unflattering for the sitter. In 1905, on a commission from the “Zolotoe Runo” (Golden Fleece) magazine, the artist created a portrait of the Symbolist poet Konstantin Balmont. “The twitchy, monkeyish figure of the poet confident of his genius is extremely expressive,”5 Grabar commented. From 1904 Serov’s favourite model was Henrietta Girshman, the hostess of a famous Moscow salon and the wife of the prominent industrialist and collector Vladimir Girshman. The story behind the creation of her portraits is the story of the search for a “grand style” grounded in the accomplishments of the masters of the past and measuring up to the demands of the new times. A gouache sketch on cardboard features the subject sitting (1904), its flowing lines in tune with modernist style. Yet Serov was not satisfied with this drawing and attempted to destroy it. In 1906 he set about working on an image of Girshman in her boudoir. A watercolour study for the portrait, on view at the exhibition, conveys the artist’s idea – to evoke Velázquez’s “Las Meninas” through the diversity of associations generated by the piece and the play on the reflections in the mirror. Grabar ranked this portrait among Serov’s best works. The artist himself was particularly fond of his final portrait of Girshman, the oval image of 1911. Serov felt that in terms of nobleness and purity of line he was finally approaching the work of masters such as Ingres and Raphael. Simultaneously with the Girshman portrait Serov was working on the portrait of Princess Paulina Shcherbatova. Different in format and purpose – a monumental and typically ceremonial portrait – it also corresponds with Serov’s stylistic explorations along neoclassical lines. Serov’s artistic quest reached far beyond the genre of the portrait. “You know, I’m a bit of a landscapist anyhow,” he wrote6. A special sensitivity to nature is felt already in the works accomplished by the artist at the age of 14 – “Mutovki Village. Near Abramtsevo” (1879), and “Akhtyrka. A House with Garden” (1879). The youth who worked by Repin’s side in those years adopted his mentor’s style, but the affectionate attitude to certain individual areas in natural environment and attention to ТРЕТЬЯКОВСКАЯ ГАЛЕРЕЯ / THE TRETYAKOV GALLERY / #1’2012 89 CURRENT EXHIBITIONS detail make his sketches resemble not so much Repin’s work as Ivan Shishkin’s pencilled drafts. Interestingly, Serov chose seemingly mundane narratives which many other artists of the time would have overlooked. Such is the drawing of a burneddown house that he saw shortly before Christmas from a window of Repin’s aparment (“After a Fire”, 1890). Abramtsevo, the Mamontovs’ estate, as well as Domotkanovo, bought by Vladimir Derviz, who was a friend of Serov and the husband of his sister, were not just retreats for emotional rest. In these hideouts Serov created such landscapes as “A Village” (1898), “A Grey Day” (1898), and “Colts by a Watering Hole” (1904), whose lyricism and unpretentious beauty place them in the same category as Isaac Levitan’s works. Serov’s landscapes invariably feature people and animals. One of his most compelling and unusual pieces is a chalk drawing “Percherons” (1909), the result of an argument with his sister Nina SimonovichYefimova about who would better draw a horse by memory. The outcome of this “duel” was pre-determined: Serov finely 90 ВЫСТАВКИ captured the singular shapes and motions of the French draft horses. Serov, who never abandoned his artistic quest, was equally versatile when he tackled landscapes, and the evolution of his style is traceable in his watercolours. Starting out with naturalist and detailed landscapes, over the years the artist evolved toward a more generalized approach and to neat colour spots (“Landscape. Near the Fence Round a Village”, 1900s; “A Carriage”, 1908). Already in the 1890s Serov came up with a remarkably impressive drawing of a coachman disappearing in a snowstorm (“A Coachman”, from the 1890s) – an ephemeral one-tone watercolour image. Serov was able with just a few strokes of the brush to create the forms of the landscapes of Greece that enthralled him, as in the crest of a cliff or an overrunning wave (“Greece. A Landscape”, “Greece. The Island of Crete”, both from 1907). Sometimes the artist made variations on a single composition using different media. It is interesting to compare his famed pastel “A Peasant Woman with a Horse” (1898) and an etching of the same ТРЕТЬЯКОВСКАЯ ГАЛЕРЕЯ / THE TRETYAKOV GALLERY / #1’2012 Натурщица. 1905 Картон, уголь, темпера. 68 ¥ 63 восьмиугольник A Model. 1905 Carbon and distemper on cardboard 68 ¥ 63 cm octagonal 7 Serov. Memoirs, Journals, Letters of His Contemporaries. Vol. 1. P. 438. title from 1899, commissioned by the “Mir Isskustvo” (World of Art) magazine. Taking in consideration the characteristics of etching as a medium, the artist replaced the pastel softness of lines with energetic black strokes contrasting with the white surface of the sheet. Serov’s landscapes created in the open air are closely linked with his compositions on themes from Russian history. Accurate in historical details, the artist was eager to bring to life images of the past using landscape as a way to introduce elements of reality into his paintings. Serov first engaged with a historical subject in the 1900s when preparing illustrations to Nikolai Kutepov’s book “How Tsars and Emperors Hunted in Rus. Late17th and 18th Centuries”. This commission inspired paintings the drafts of which – “Going Out On a Hunt (Peter II and Tsarevna Yelizaveta Petrovna Hunting with Dogs)” (1900), and “Catherine II Going Out On a Hunting Excursion with Falcons” (1900-1902) – are held at the Tretyakov Gallery. Interestingly, in each case the artist in search of a suitable narrative chose not the distinctive moment when the hunt for animals was in progress but the preceding episode when the hunters had arrived at the scene. Serov, who was not an enthusiastic hunter himself, was interested most of all in realist depiction of life in the 18th century. Serov was especially interested in the personality of Peter I. Together with Alexander Benois, another enthusiast of the “Petrine era”, he visited the palaces outside St. Petersburg built in the 18th century and the era’s museums (at the Hermitage the artist made drawings of all of the Emperor’s surviving clothes and studied his death mask). The perfectly preserved interior setting of Peter I’s little home “Monplaisir”, in Peterhof, inspired Serov for the creation of “Peter I in Monplaisir” (1910-1911), the first draft of which was created in 1903. By then the artist already had the idea to represent the Tsar at the moment when, just awakened from sleep, he has walked up to the window. “He just rose from the bed, didn’t sleep well, he’s ill, the face is green,”7 as the artist explained his vision. This naturalist detail was needed to elevate the image to the level of painting made from nature, to add the veracity of a portrait. In 1906 Iosif Knebel invited Serov to create an image of Peter I at the time of the construction of St. Petersburg for a book called “Images of Russian History” (Moscow, 1908). The artist became fascinated with the subject and until late in his life returned to it again and again, producing new versions, the most famous among them a gouache “Peter I” (1907). Serov wanted to show a real person, not the embellished image of a monarch. “It’s a pity,” he said, “that this person, who had nothing pretentious or sickeningly sweet about him, has always been portrayed as the hero of an opera and physically attractive. But he was ugly: a следованием натуре. В них заметно влияние И.Е. Репина, у которого Серов в те годы брал частные уроки. В 1880 году, несмотря на юный возраст (менее положенных 16 лет), Серов поступает в Императорскую Академию художеств и начинает обучение в мастерской П.П. Чистякова. Академический метод рисования трудно давался привыкшему к вольному репинскому штриху юноше, зато Чистяков сразу отметил нового ученика. Спустя много лет, уже признанный мастер, Серов признавался наставнику: «Помню Вас как учителя и считаю Вас единственным (в России) истинным учителем вечных незыблемых законов формы, чему только и можно учить…»1 К периоду занятий у Чистякова относится рисунок с изображением уснувшего Ю.П. Таньона – бывшего гувернера и друга семьи Мамонтовых (1884). Следование сформулированным Чистяковым постулатам – внимательному исследованию натуры и постижению искусства великих художников прошлого – всегда останется в основе собственного метода рисования Серова. Многие часы он провел в Эрмитаже, копируя творения Рембрандта, Веласкеса, Веронезе. Как правило, это не «дословные» копии, а свободная авторская интерпретация шедевра. Такова знаменитая акварель «Венера перед зеркалом» (1890-е), исполненная с картины Тициана2. Еще в период обучения в ИАХ натурные штудии стали играть особую роль в совершенствовании мастерства Серова-рисовальщика. Его акварельные натурщицы, исполненные в классах Московского училища живописи, ваяния и зодчества уже в бытность преподавателем, – это самоценные произведения, далекие от сухих академических постановок. В собрании Третьяковской галереи имеется несколько изображений «любимой натурщицы Серова» (по воспоминаниям М.Ф. Шемякина) Веры Ивановны3. Каждый раз художник создает разные образы, то напоминающие Г.Л. Гиршман (поворотом головы, пышной прической и изящными туфельками), то лаконичностью и колоритом отсылающие к произведениям на античные темы («Похищение Европы», 1910). До последних лет Серов упражнялся в оттачивании линии и формы, рисуя с натуры. В 1910–1911 годах он наравне с начинающими художниками посещает студии Жюльена и Коларосси в Париже. Опыт работы с натуры и привычка к многочасовым сеансам рисования модели – основа мастерства Серова-портретиста. В 1900-е годы к художнику приходит всеобщее признание, а с ним и многочисленные заказы на портреты. Постоянное стремление к освоению новых форм и стилей не позволило Серову «растратить талант» на бесконечный поток модных портретов. Каждый раз мастер ставит перед собой новую задачу, Портрет Г.Л. Гиршман. 1906 Бумага, акварель, белила 38,5 ¥ 37,8 Portrait of Henrietta Girshman. 1906 Watercolour and white paint on paper 38.5 ¥ 37.8 cm пытаясь уловить самое характерное в модели и воплотить это в своей работе. По заказу видного промышленника А.Н. Ратькова-Рожнова был исполнен портрет С.М.Лукомской (1900). «Сила ее выразительности настолько велика, – писал И.Э.Грабарь, – что один из известнейших французских психиатров, увидя фотографию с акварели, точно определил психическое состояние модели, тогда уже заболевшей тяжелым недугом»4. Портреты Серова всегда отличались меткостью характеристики, порой нелестной для изображенного. В 1905 году для журнала «Золотое Руно» художник исполнил портрет символиста К.Д.Бальмонта. «Издерганная, кривля- 1 Валентин Серов в переписке, документах, интервью. В 2 т. Т. II. Л., 1989. С. 151 (далее – Серов в переписке, документах, интервью). 2 Картина Тициана находилась в собрании Эрмитажа, в 1931 году была продана в США, ныне находится в Национальной галерее искусств (Вашингтон). 3 Валентин Серов в воспоминаниях, дневниках и переписке современников. В 2 т. Л., 1971. Т. II. С. 230 (Далее – Серов в воспоминаниях, дневниках и переписке современников). 4 Грабарь И.Э. Валентин Александрович Серов: Жизнь и творчество. 1865–1911. М., 1965. С. 336 (далее – Грабарь. 1965). 5 Там же. С. 174. ющаяся фигура поэта, уверенного в своей гениальности, предельно выразительна»5, – отозвался Грабарь. С 1904 года любимой моделью Серова становится Г.Л. Гиршман, хозяйка известного московского салона, жена крупного промышленника и коллекционера В.О. Гиршмана. История создания ее портретов – это история поиска «большого стиля», опирающегося на достижения мастеров прошлого и отвечающего запросам нового времени. Набросок гуашью на картоне, изображающий сидящую Гиршман (1904), плавностью линий созвучен стилистике модерна. Однако Серов не был удовлетворен этим рисунком и пытался его уничтожить. В 1906 он приступил к работе над портретом Гиршман в интерьере ее будуара. Акварельный эскиз портрета, представленный на выставке, передает замысел художника, многоплановостью композиции и игрой с отражением в зеркале вызывающий ассоциации с «Менинами» Веласкеса. Грабарь причислил портрет к лучшим произведениям Серова. Сам же художник особенно был доволен последним, овальным портретом Гиршман (1911). Серов чувствовал, что по благородству и чистоте линий он, наконец, приближается ТРЕТЬЯКОВСКАЯ ГАЛЕРЕЯ / THE TRETYAKOV GALLERY / #1’2012 91 CURRENT EXHIBITIONS Портрет Ф.И. Шаляпина. 1905 Холст, уголь, мел. 235 ¥ 133 Portrait of Feodor Ivanovich Chaliapin. 1905 Charcoal, chalk on canvas 235 ¥ 133 cm 92 ТРЕТЬЯКОВСКАЯ ГАЛЕРЕЯ / THE TRETYAKOV GALLERY / #1’2012 ВЫСТАВКИ к произведениям таких мастеров, как Энгр и Рафаэль. Параллельно мастер работал над портретом княгини П.И. Щербатовой. Иной по формату и назначению – монументальный, типичный парадный портрет, – он также отвечает стилистическим исканиям Серова в духе неоклассики. Творческие поиски Серова выходили далеко за рамки портретного жанра. «Я ведь все-таки немного и пейзажист», – говорил он6. Особое отношение к природе чувствуется уже в рисунках 14-летнего художника – «Деревня Мутовки. В окрестностях Абрамцева» (1879), «Ахтырка. Дом с садом» (1879). Работавший в эти годы бок о бок с И.Е. Репиным, юноша хоть и перенимает манеру учителя, однако любовным отношением к отдельно взятым уголкам природы и тщательной проработкой его зарисовки напоминают, скорее, карандашные этюды И.И. Шишкина. Интересно, что Серов выбирает обыденные на первый взгляд сюжеты, мимо которых прошли бы многие художники того времени. Таков рисунок сгоревшего дома, увиденного им под Рождество из окна репинской квартиры («После пожара», 1880). Усадьба Мамонтовых Абрамцево, а позже и Домотканово, приобретенное В.Д. Дервизом, другом и мужем сестры, служили Серову не только местами душевного отдохновения. Там были созданы пейзажи «Деревня» (1898), «Серый день» (1898), «Стригуны на водопое» (1904), не уступающие своей лиричностью и неброской красотой творениям И.И. Левитана. Отличительная особенность пейзажей Серова – неизменное присутствие в них людей и животных. Особый интерес представляет угольный рисунок «Першероны» (1909), результат спора с сестрой, Н.Я. Симонович-Ефимовой, о том, кто лучше нарисует лошадь по памяти. Исход этой своеобразной «дуэли» был заранее предрешен, Серов тонко уловил своеобразную пластику французских тяжеловозов. Пребывавший в постоянном художественном поиске Серов разнообразен и в интерпретации пейзажной темы. Эволюция его стиля заметна в акварелях. От натуралистичных и подробных пейзажей художник с годами движется к большему обобщению, к работе лаконичным цветовым пятном («Пейзаж. У околицы», 1900-е; «Карета», 1908). Уже в 1890-е появился удивительный по выразительности рисунок исчезающей в метели фигуры извозчика («Извозчик»), эфемерный, исполненный акварелью в один тон. Серову достаточно всего нескольких ударов кистью, чтобы обозначить впечатлившие его пейзажи Греции – хребет скалы или набежавшую волну («Греция. Пейзаж», «Греция. Остров Крит»; оба – 1907). Порой одну и ту же композицию мастер воплощал в различных техниках. Таньон, спящий на стуле. 1884 Бумага, графитный карандаш, итальянский карандаш, прессованный уголь 48,2 ¥ 34,2 Mr. Tagnon Sleeping on a Chair 1884 Graphite pencil, Italian pencil and pressed chalk on paper. 48.2 ¥ 34.2 cm 6 Цит. по: Грабарь И.Э. Серов. М., 1914. С. 82 (далее – Грабарь. 1914). 7 Серов в воспоминаниях, дневниках и переписке современников. Т. I. С. 438. Интересно сопоставить знаменитую пастель «Баба с лошадью» (1898) и одноименный офорт (1899), исполненный по заказу редакции журнала «Мир искусства». Художник исходит из особенностей гравюры и заменяет пастельную мягкость линий энергичным черным штрихом, контрастирующим с белым полем листа. Натурные пейзажи Серова неразрывно связаны с композициями на тему русской истории. Соблюдая верность историческим деталям, художник стремился оживить образы прошлого, внося в картину элемент реальности благодаря пейзажу. Впервые к исторической теме Серов обратился в 1900-х годах в связи с работой над иллюстрациями к изданию Н.И. Кутепова «Царская и императорская охота на Руси. Конец XVII и XVIII век». Заказ на иллюстрации послужил поводом к написанию картин, эскизы которых – «Выезд на охоту (Петр II и цесаревна Елизавета Петровна на псовой охоте» (1900), «Выезд Екатерины II на соколиную охоту» (1900–1902) – хранятся в собрании Третьяковской гале- реи. Интересно, что в обоих случаях при выборе сюжета художник избрал не характерный момент погони за зверем, но предшествующую ему сцену выезда охотников. Серова, не увлекавшегося охотой, в первую очередь интересовала возможность достоверного отображения жизни XVIII столетия. Личность Петра I вызвала у Серова особый интерес. Вместе с А.Н. Бенуа, также увлеченным Петровской эпохой, он посещал загородные дворцы XVIII века и музеи (в Эрмитаже художник перерисовал весь сохранившийся гардероб императора, изучал его посмертную маску). Идеально сохранившаяся обстановка петровского домика Монплезир в Петергофе вдохновила Серова на создание композиции «Петр I в Монплезире» (1910–1911). Ее первый вариант относится к 1903 году. Уже тогда сложился замысел представить Петра в тот момент, когда, только проснувшись, он подошел к окну. «…Он только что встал, не выспался, больной, лицо зеленое»7, – объяснял художник свой замысел. Эта натуралистическая деталь была ТРЕТЬЯКОВСКАЯ ГАЛЕРЕЯ / THE TRETYAKOV GALLERY / #1’2012 93 CURRENT EXHIBITIONS Диана и Актеон 5 1911 Бумага, графитный карандаш, акварель 43 ¥ 27 ВЫСТАВКИ Аполлон и Диана, 6 избивающие детей Ниобеи. 1911 Бумага, акварель, черный карандаш 25,4 ¥ 45,4 Apollo and Diana 6 Killing Niobe’s Children. 1911 Watercolour and black pencil on paper 25.4 ¥ 45.4 cm Diana and Actaeon 5 1911 Watercolour and graphite pencil on paper. 43 ¥ 27 cm spindling… who also walked in huge strides, and all his companions had to run in order to keep pace with him.”8 In 1910-1911 the artist worked on a new version of the image. The key idea remained the same – to show the ever-hurrying and awe-inspiring Peter who is impatient of his slothful subjects. In this composition the Tsar was depicted heading to a construction site on a cart and threateningly brandishing his huge fist in the face of an idly strolling peasant. Serov reached his zenith as an artist at the time when the “World of Art” group was being established, and he was a friend to, and worked in cooperation with, many of its members. The artist’s engagement with the historical theme corresponded with the fascination with the past felt by the “World of Art” artists. But an even stronger tie between Serov and the group was formed by their shared interest in theatre. The artist had mixed with theatre people since his childhood: the Moscow home of his parents, the famous composer and music critic Alexander Serov and his mother, the talented piano player Valentina Bergman-Serova, was visited by musicians, actors and artists. Later, befriending the Mamontov family and establishing close rapport with the members of the Abramtsevo colony, Serov, too, could not resist theatre, which was Savva Mamontov’s passion. Together with Vasily Polenov and Mikhail Vrubel, Serov painted backdrops for amateur productions in Abramtsevo and participated in them himself, displaying a remarkable acting talent. In 1900 Serov helped Vrubel to paint a gigantic curtain for Mamontov’s private opera house. His first large theatre project was designing sets for a production of Alexander Serov’s opera “Judith” at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg in 1908-1909 (it premiered on November 10 1908). Initially Konstantin Korovin had been recruited for the job but Serov was dissatisfied with what he did, believing that the sets were “stripped of that modest degree of nobleness”9 which had been present in his sketches. The next, and the last, pro- duction which Valentin Serov designed was Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s ballet “Scheherazade” for Sergei Diaghilev’s “Ballets Russes” season in Paris. The artist himself offered his services in painting the curtain for a production which had already premiered. The curtain, in the style of Iranian miniatures, was completed in Paris between late May and early June 1911, together with the sculptor Ivan Yefimov and his wife, the artist Nina Simonovich-Yefimova. Serov wrote to Ilya Ostroukhov: “I had two weeks to finish my Persian curtain, which I did. I had to work from 8 in the morning till 8 at night (I have never before worked at such pace). Both our gentlemen artists and some French colleagues say the curtain came out fairly well. Dryish, but not ignoble, unlike Bakst’s saccharine sumptuousness.”10 Interestingly, in this period he was again especially concerned about the “nobleness” of the production. Serov’s achievements as a stage designer are modest, but his close ties with this art form found expression in a series of portraits of prominent theatre personalities. In 1909-1910 he produced several drawings distinguished by the amazing clarity of their forms, featuring female dancers of the Diaghilev company (Tamara Karsavina and Anna Pavlova), and created distinctive studies for the famous portrait of Ida Rubinstein. Serov had known Konstantin Stanislavsky personally from an early age, and they participated in the same amateur productions in the Mamontovs’ home and later would come to share many views on the mission of art. Two tenets of the Stanislavsky system – “stimulating emotions through physical actions” and “living the part one is playing”11 – can be easily applied to Serov’s oeuvre as well. In 1911 he created a portrait of the great director: the artist looks up at his model from below, as if this person is on a stage and slightly towers over the viewer. The same technique was used in the monumental portrait of Feodor Chaliapin from 1905. Serov reconsidered the principles of the ceremonial portrait, applying them not to the image of an aristocrat, as had been standard practice before, but to that of a prominent actor. Another example of the use of neat graphic lines in a monumental piece was a poster for a production of “Les Sylphides” with Anna Pavlova (1909, Russian State Library). “Pavlova’s portrait by Serov received more reviews in the press than Pavlova herself,”12 the critic Lavrenty Novikov wrote in his memoirs. 8 Grabar, 1914. P. 248. 9 Serov. Correspondence, Documents, Interviews. P. 152. 10 94 ТРЕТЬЯКОВСКАЯ ГАЛЕРЕЯ / THE TRETYAKOV GALLERY / #1’2012 Ibid., pp. 298–299. 11 Grabar, 1965. P. 282. 12 Serov. Memoirs, Journals, Letters of His Contemporaries. Vol. 2. P. 473. призвана возвысить сочиненное изображение до уровня картины, сделанной с натуры, добавить портретной убедительности. В 1906 году И.Н. Кнебель предложил Серову создать композицию, представляющую царя-реформатора в период строительства Петербурга, для издания серии школьных пособий «Картины по русской истории» (М., 1908). Тема необычайно увлекла художника, до последних лет жизни он возвращался к ней, создавая новые варианты. Наибольшую известность получила гуашь «Петр I» (1907). Серов хотел показать реальную личность, а не приукрашенный образ монарха. «Обидно, – говорил он, – что его, этого человека, в котором не было ни на йоту позы, слащавости, всегда изображают каким-то оперным героем и красавцем. А он был страшный: долговязый… при этом шагал огромными шагами, и все его спутники принуждены были следовать за ним бегом»8. В 1910– 1911 годах художник работал над новой трактовкой темы. Основная идея осталась той же – показать вечно спешащего грозного Петра, сурового по отношению к нерадивым подданным. На этот раз император был изображен едущим в телеге на работы и грозящим огромным кулаком праздношатающемуся мужику. Годы расцвета творчества мастера пришлись на время создания объединения «Мир искусства», с членами которого он сотрудничал и дружил. Обращение Серова к исторической теме соответствовало увлечению мирискусников минувшими эпохами. Еще более их сближал интерес к театру. Театральная среда была близка художнику с детства. В доме его родителей, известного композитора и музыкального критика А.Н.Серова и талантливой пианистки В.С.Бергман-Серовой, в Москве бывали музыканты, артисты, художники. Позже, сблизившись с семьей Мамонтовых и тесно общаясь с членами Абрамцевского художественного кружка, Серов также не мог оставаться в стороне от театра, страстно любимого С.И. Мамонтовым. Вместе с В.Д. Поленовым и М.А. Врубелем Серов писал декорации для домашних постановок в Абрамцеве и сам участвовал в них, проявляя недюжинный актерский талант. В 1900 году он помогал Врубелю в написании огромного занавеса для Русской частной оперы Мамонтова. Его первая масштабная работа для театра – оформление оперы А.Н. Серова «Юдифь», поставленной на сцене Мариинского театра в Петербурге в 1908 году. Исполнение декораций было поручено К.А. Коровину, однако Серов остался недоволен, сочтя, что декорации лишились «той небольшой доли благородства»9, которая имелась в его эскизах. Следующая и последняя работа мастера по оформлению спектакля была связана с балетом на музыку Н.А. Римского-Корсакова «Шехеразада» для Русских сезонов Натурщица. 1904 Картон, воск, акварель, белила, черный карандаш, графитный карандаш. 37,9 ¥ 31,7 Изображение очерчено A Model. 1904 Graphite pencil, black pencil, white paint, watercolour, wax on cardboard 37.9 ¥ 31.7 cm The figure is contoured 8 Грабарь. 1914. С. 248. 9 Валентин Серов в переписке, документах, интервью. С. 152. 10 Там же. С. 298–299. 11 Грабарь. 1965. С. 282. 12 Серов в воспоминаниях, дневниках и переписке современников. Т. II. С. 473. С.П.Дягилева в Париже. Художник сам вызвался написать занавес к уже осуществленной постановке. Занавес в стиле иранских миниатюр был исполнен в Париже в конце мая – начале июня 1911 года совместно со скульптором, графиком и живописцем И.С.Ефимовым и его женой художницей Н.Я.Симонович-Ефимовой. Серов писал Остроухову: «…я в две недели должен был написать свой персидский занавес, который и написал. Пришлось писать с 8 утра до 8 вечера (этак со мной еще не было). Говорят, неплохо, господа художники как наши, так и французские некоторые. Немножко суховато, но не неблагородно в отличие от бакстовской сладкой роскоши»10. Интересно, что и в этот раз его особенно волновал вопрос благородства постановки. История сотрудничества Серова с театром в качестве оформителя небогата, однако его тесная связь с этой сферой искусства выразилась в череде портретов людей, принадлежащих к театральной среде. В 1909–1910 годах он создал ряд удивительных по своей графической чистоте изображений танцовщиц Русских сезонов (Тамары Карсавиной, Анны Павловой) и острые характерные наброски к знаменитому портрету Иды Рубинштейн. С детства Серов был знаком с К.С. Станиславским, они вместе участвовали в театральных постановках в до- ме Мамонтовых, позже их объединяли сходные взгляды на задачи искусства. Два главных принципа системы основателя Московского Художественного театра – «поиски характерного и переживание воплощаемого образа»11 –можно с легкостью отнести и к творчеству Серова. В 1911 году он исполнил портрет Станиславского. Художник избрал точку зрения снизу, словно изображенный находится на сцене, слегка возвышаясь над зрителем. Тот же прием использован и в монументальном портрете Ф.И.Шаляпина (1905). Серов переосмыслил схему парадного портрета, применив ее для изображения не аристократической персоны, как было принято, но выдающегося артиста. Другим примером использования лаконичной графической линии в монументальной форме стал плакат-афиша балета «Сильфиды» с участием Анны Павловой (1909, РГБ). «Портрет Павловой работы Серова вызвал больше откликов в печати, чем сама Павлова»12, – заметил в своих воспоминаниях Л.Л.Новиков. Поиски в области монументальных форм – одна из основных тем творчества мастера в последние годы. Нередко они были связаны с разработкой мифологических сюжетов, обращением к искусству Древней Греции. Планы по оформлению греческих залов Музея изящных искусств (ныне ГМИИ им. ТРЕТЬЯКОВСКАЯ ГАЛЕРЕЯ / THE TRETYAKOV GALLERY / #1’2012 95 CURRENT EXHIBITIONS ВЫСТАВКИ Петр I на работах. Строительство Петербурга 1910–1911 Бумага, черный карандаш, мел 57 ¥ 83,3 Peter I on a Construction Site. The Construction of St. Petersburg 1910-1911 Black pencil and chalk on paper 57 ¥ 83.3 cm Петр I на работах. Строительство Петербурга 1910–1911 Картон, гуашь 57 ¥ 83,3 Peter I on a Construction Site. The Construction of St. Petersburg 1910–1911 Gouache on cardboard. 57 ¥ 83.3 cm Such explorations in monumental genres were one of the artist’s main preoccupations in his last years. Often these projects featured the myths and themes from the art, of Ancient Greece. Serov’s plans for designing the Greek rooms at the Museum of Fine Art (now the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts) in 1902, and then his travel to Greece together with Bakst in 1907, inspired him for the creation of images rich with references to Greek antiquity. “The Rape of Europa” (1910) is a painting themed on one of the pivotal myths of Aegean civilizations. In the same way as he did working on images from Russian history, the artist was eager to combine naturalist drawing and symbolic imagery. He created a decorative mural but at the same time sparked life in the mysterious Kore, depicting her as a creature moving and gesturing like a real woman. The artist looked everywhere for an animal on which to model the bull, which, according to the legend, was a reincarnation of Zeus, and only in Italy, on a farm in Orvieto did he find what he needed. At the same time the artist was working on another image related to Greek 96 mythology, “Odysseus and Nausicaa”13. Already in 1903 he had told Benois that he was interested in painting Nausicaa, although “not in the manner she’s usually represented, but the way she really was”14. As in the case of “The Rape of Europa”, Serov came up with several versions of “Odysseus and Nausicaa”. The current exhibition features a horizontal sketch imaging a procession traced in ink. A more developed draft, in gouache, is distinguished by its warm palette and the frame with a herringbone motif that Serov borrowed directly from Aegean art. Yet another version was made using gouache and distemper. Whereas the previous version resembles a monumental frieze, the distemper picture is an independent work of art with balanced proportions, featuring the procession against a high sky of pearly and grey hues. The artist’s daughter reminisced that these pieces had different colour schemes because Serov worked on some of them in Finland, this creating the soft greyish-blue colours. The artist never completed his innovative pieces, which he envisioned as themed on Greek antiquity but grounded in modernity. “The work on the paintings ТРЕТЬЯКОВСКАЯ ГАЛЕРЕЯ / THE TRETYAKOV GALLERY / #1’2012 fairly exhausted Serov, and in 1911 he did not touch them, as if abandoning them altogether”15. Perhaps Serov put “Odysseus and Nausicaa” and “The Rape of Europe” on the shelf with a view of continuing them later, and only for a commission that agreed well with Serov’s interest in exploring ancient Greek themes in monumental art. In 1910 a mansion of the Nosov family in Moscow was being renovated in “a classical style” after a design of Ivan Zholtovsky. Artists such as Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, Konstantin Somov and Alexander Benois were enlisted to design the interior. Serov was commissioned for murals for the dining room referencing Ovid’s “Metamorphoses”. In his habitual manner, the artist worked on this subject conscientiously, creating many sketches and studies for the mural. The idea was to produce a composition consisting of three sections ingeniously separated by caryatids in the form of fauns, as architectural partitions. With some variations, the composition was to be centred around such subjects as “Diana and Actaeon”, “Eros, Apollo and Daphne”, and “Venus”. It is hard to say what sort of decision Serov would finally have made, but all of his sketches evidence “that dedication to simplification of lines and forms which was characteristic for Serov’s explorations in his last year”16. His work on illustrations for Ivan Krylov’s fables became for Serov a “laboratory of exploration”17 of that sought-after line, ideal in its neatness and sharpness of characterisation. The artist worked on this project from 1895 until the last days of his life. As Vsevolod Dmitriev keenly observed, “only in his drawings and favourite fables could Serov move on to his cherished ideals so boldly and without deviation, because his contemporaries did not control him here and because they considered these pieces peripheral, marginal to his art”18. The show presents 12 main themes which the artist selected for the publication titled “12 Drawings of Valentin Serov for the Fables of Ivan Krylov” which he planned, as well as drawings for other fables and numerous sketches from nature revealing Serov as a brilliant painter of animal life. The exhibition “Valentin Serov. The Line of Life” covers many subjects, as the artist did in his work. Contrary to all mathematical rules, the short line of his life is analogous to the line of his artwork which goes on to infinity, and traverses every main artistic trend of the late-19th and early20th centuries. 13 Themed on Book 6 of Homer’s “Odyssey”. 14 Ernst, Sergei. “V[alentin].A[lexandrovich].Serov”. Petrograd: 1921. P. 67. 15 16 Grabar, 1965. P. 231. Ibid., p. 286. 17 Kruglov, Vladimir. ‘Serov’s art as reflected in the collection of the Russian Museum’. Online at: http://www.virtualrm.spb.ru/ru/resources/galleries/serov_grm 18 Dmitriev, Vsevolod. “Valentin Serov”. Petrograd, 1916. Pp. 43-44. А.С. Пушкина) в 1902 году, а затем и поездка в Грецию вместе с Л.С.Бакстом в 1907-м послужили поводом к созданию произведений на античную тему. «Похищение Европы» (1910) – картина на сюжет мифа, который играл основополагающую роль в крито-микенской культуре. Как и в процессе создания исторических картин, художник стремился объединить натурные наблюдения с символическими образами. Он создает декоративное панно, но в то же время оживляет таинственную кору, придав ей пластику реальной женщины. Повсюду художник ищет быка, с которого можно было бы написать перевоплотившегося Зевса, и лишь в Италии, на ферме в Орвието, находит подходящую натуру. Одновременно мастер работал над другим произведением на античную тему – «Одиссей и Навзикая»13. Еще в 1903 году он признался Бенуа, что ему бы хотелось написать Навзикаю, но «не такой, как ее пишут обыкновенно, а такой, какой она была на самом деле»14. Как и в случае с «Похищением Европы», существует несколько вариантов композиции «Одиссей и Навзикая». На выставке представлен эскиз горизонтального формата с намеченным тушью мотивом шествия. Более проработанный вариант, выполненный гуашью, отличает теплый колорит и обрамляющий орнамент «елочка», который был заимствован Серовым непосредственно из крито-микенского искусства. Иной по трактовке – рисунок, выполненный гуашью и темперой. Если вариант с орнаментом напоминает монументальный фриз, то темперный – это станковая картина, уравновешенная по пропорциям, шествие в ней разворачивается на фоне высокого жемчужно-серого неба. По воспоминаниям дочери художника, разница в колорите этих произведений объясняется тем, что над некоторыми из них Серов работал в Финляндии, отсюда и нежная серовато-голубая гамма. Новаторские замыслы мастера по созданию произведений, отсылающих к античности и в то же время современных, так и не были окончательно воплощены. «Работа над картинами порядком измучила Серова, и в 1911 году он их не трогал, как будто бы забросив»15. Возможно, темы «Одиссея и Навзикаи» и «Похищения Европы» были оставлены лишь на время, и то ради заказа, соответствовавшего интересу Серова к воплощению античной темы в монументальных образах. В 1910 году по проекту И.В. Жолтовского реконструировался «в классическом вкусе» особняк В.В. и Е.П. Носовых в Москве. К оформлению интерьеров были привлечены М.В.Добужинский, К.А.Сомов, А.Н.Бенуа. Серову была заказана роспись столовой на сюжеты из «Метаморфоз» Овидия. По обыкновению художник с большим вниманием подошел к разработке этой темы, он оставил множество эски- Боярин на охоте 1890-e Бумага, акварель, гуашь 46 ¥ 33 A Boyar Hunting 1890s Gouache and watercolour on paper 46 ¥ 33 cm зов и альбомных набросков с вариантами росписи. Замысел заключался в создании трехчастной композиции, остроумно разделенной кариатидами-фавнами или архитектурными членениями. Основными избранными сюжетами с некоторыми вариациями были: «Диана и Актеон», «Эрот, Аполлон и Дафна», «Венера». Сложно судить о том, к какому решению пришел бы Серов в итоге, но во всех эскизах прослеживается «то стремление к упрощенности линий и форм, которое характерно для последнего года серовских исканий»16. «Лабораторией поиска»17 той самой линии, идеальной по своей лаконичности и остроте характеристики, стали для Серова иллюстрации к басням И.А.Крылова. Работу над ними художник вел с 1895 года и до последних дней жизни. Как метко подметил В.А. Дмитриев, «…только в рисунках и в любимых баснях Серов мог безбоязненно и прямо идти к заветным идеалам, так как современники здесь его не контролировали, так как эти вещи казались современникам второстепенными, побочными в серовском творчестве»18. На выставке представлены 12 основных сюжетов, которые художник отобрал для планируемого им издания «Двенадцать рисунков В. Серова на басни И.А. Крылова», а также рисунки к другим басням и многочисленные наброски с натуры, открывающие зрителю Серова как блестящего анималиста. Выставка «Валентин Серов. Линия жизни» многозначна, как и само творчество мастера. Короткая линия его жизни, вопреки всем математическим законам, тождественна стремящейся к бесконечности линии творчества, проходящей через все основные художественные направления конца XIX – начала XX века. 13 На сюжет из «Одиссеи» Гомера (Песнь шестая). 14 Эрнст С.Р. В.А.Серов. Пг., 1921. С. 67. 15 Грабарь. 1965. С. 231. 16 Там же. С. 286. 17 Круглов В.Ф. Творчество Серова в зеркале коллекции Государственного Русского музея. http: // www.virtualrm.spb.ru/ru/resources/galleries/serov_grm 18 Дмитриев В. Валентин Серов. Пг., 1916. С. 43–44. ТРЕТЬЯКОВСКАЯ ГАЛЕРЕЯ / THE TRETYAKOV GALLERY / #1’2012 97