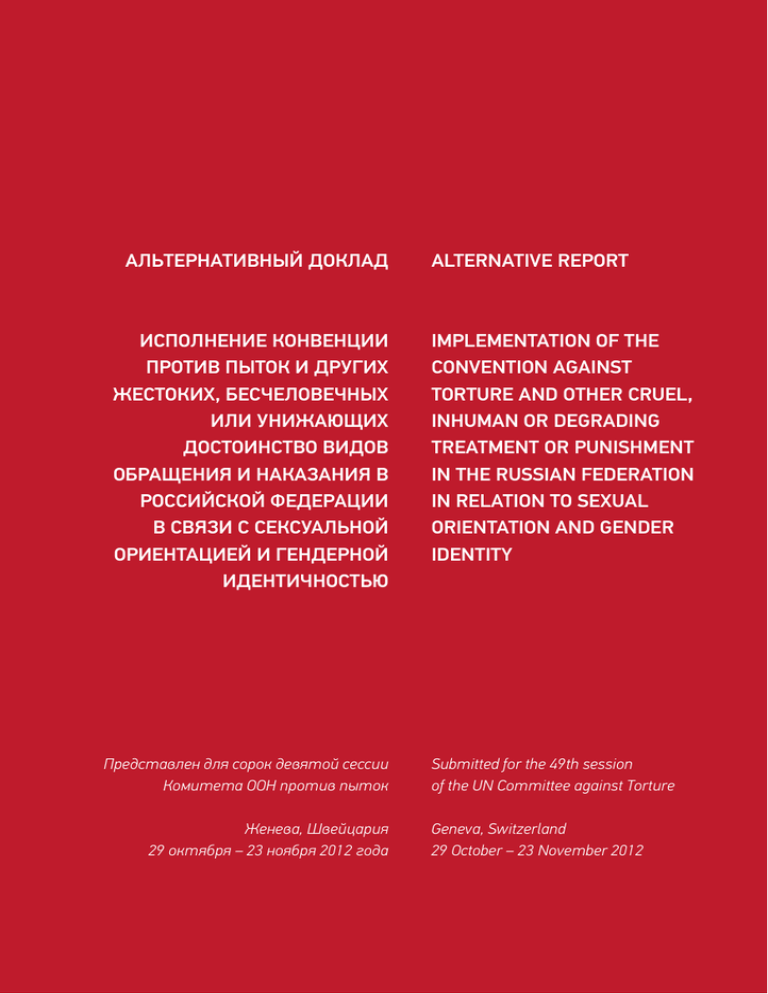

альтернативный доклад исполнение конвенции против

реклама